Doomsday for 2026 is ... SATURDAY

Knowing this can give you the day of the week for any date in 2026.

For the details:

Knowing this can give you the day of the week for any date in 2026.

For the details:

Reprinting a “lost” post that somehow got dropped during migration to Micro.blog many years ago.

In response to Michael’s post of recommended films, here’s my list of the various media we’ve been ingesting (movies, TV, books, performances) the last several months. Not all are enthusiastically recommended. But maybe you will get a sense of what I like and don’t like, and can then judge whether to trust my appraisals. This is one value that critics and reviewers provide, if nothing else Movies were seen via Netflix, Amazon Prime, or at the mighty Carolina Theatre.

God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man : a saltwater Geechee talks about life on Sapelo Island by Cornelia Bailey with Christena Bledsoe (2000). I read to Liz before she goes to sleep and we’ve found over the years that memoirs tend to be our favored material. This book is an oral history told by Bailey about her life on the Georgia barrier island of Sapelo, populated by the descendants of slaves who had worked cotton on the island. The memoir covers her life from when she was born in the ’50s to the present-day, with lots of cultural history and stories going back to pre-Civil War times. Even in the ’50s, the inhabitants lived in a supernatural world alongside the natural one; she talks about “haints,” interpreting dreams, and the ghosts of dead ancestors always close by as daily companions. Bailey’s easy way with a story and lively memories make this a delightful reading experience. We’ve not gotten there yet, but we will soon hear about the decline of the old ways as the young move off of the island and the few residents who remain fight off pressure from the State of Georgia, which owns nine-tenths of the island. The book’s title derives from the Geechees’ (cousin to the Gullahs) belief in the equal power of God, “Dr. Buzzard” (voodoo), and the “Bolito Man” (luck).

Tig (dirs: Kristina Goolsby, Ashley York, 2015). A documentary of standup comedian Tig Nitaro, who lived through one of the most hellish years one could imagine and her struggles with transforming some of those experiences into jokes and material, along with rebuilding her life and career. I don’t want to say more, as I came to this knowing nothing of her struggles; as her story would turn a corner and go somewhere new and unexpected, I was swept along and as shocked or delighted as she was. Her bravery in so many aspects of her life – not just shakily rebuilding her career but taking bigger and bigger personal chances too – had me shaking my head in admiration.

Silicon Valley, season 1 (2014). So great to have a Mike Judge TV series again and this one is so smart and so spot-on in its satire of the Silicon Valley culture. The culture is already so over the top, it’s hard to see how it can be lampooned, but Judge and his writers do it. The skeletal and spectral Jared is my favorite character. Be warned that it can be pretty raunchy, particularly the last episode.

The Overnight (dir: Patrick Brice, 2015). When did quirk become the new normal? A thin piece that, after the mysteries are explained, starts rousing to some kind of strange life – and then it’s over. Afterward, I started writing an essay in my head on how the story sets up the characters and its themes, deconstructing why do the leading ladies and leading men look alike?, and finding evidence that at film’s end things are still not as they seem … when I wondered why I was polishing my bucket to hold a drop of water. One of the quips I’ve seen all over the web lately goes, “Some things once seen cannot be unseen.” This is especially true of Adam Scott and Jason Schwartzman’s skinny-dipping scene.

Hello Ladies, the series (2013) and the movie (2014). How much of this series you can tolerate depends on how much you like the cringeworthy comedies that Stephen Merchant has created with Ricky Gervais. His hapless ladies’ man and lame cool guy routine gets routine pretty quickly, while his character’s willful ignorance, inability to learn his lessons, and punishing trials never seem to go further than trying to raise a larf. When I could get past the plots, though, I enjoyed watching his character Stuart hanging out with his friends and particularly his attractive tenant Jessica, and following their stories with more interest. The characters’ craving for something they can’t have blinds them all, one way or another. Merchant and his co-writers also have an uncanny ability to suggest tenderness and vulnerability peeking out from under the farce’s bedsheets. The series’ last two episodes were the high point, focusing on the characters with the comedy taking a back seat. The movie wraps up the series’ loose threads with a hackneyed plot in the first half that shifts gears in the second to a serious study of this damaged character and his redemption. I was actually cheering for him at the end. And the movie sports one of the funniest sex scenes ever, so there’s that.

Alice Gerard & Rayna Gellert, Laurelyn Dossett. We went to Duke’s Music in the Gardens series to see these great folk performers. Because live performance by real musicians is what it’s all about. Support your local artists.

Me & Earl & The Dying Girl (dir: Alfonso Gomez-Rejon, 2015). A self-absorbed white high-school boy shakes off his cloud of mope after alienating his black friend and breaking the heart of the dying girl. Oooooo-kay. What makes the movie work is its kinetic storytelling (reminded me of Thank You For Smoking, for some reason) and the movie parodies. And maybe it’s me, but I was really offended by the popular girl offering herself as Greg’s prom date. Why did these characters give Greg the time of day?

The Audience (dir: Stephen Daldry, 2013) Seen via the National Theatre’s live stream into selected movie theaters. An entertaining collection of vignettes showing Queen Elizabeth II’s relationships with her prime ministers, from Churchill to Cameron. Funny, middlebrow, fast-moving, a few piquant observations on the queen’s role in her country, Mirren is as masterly as they say, and I didn’t believe any of it for a second. I prefer The Queen (2006).

I’ll See You In My Dreams (dir: Brett Haley, 2015). So good to see Blythe Danner onscreen again, even in a posh Hallmark Channel type of movie; the supporting actors are great, the lines are funny, and Sam Elliott is sly and dry as the man who wakes Danner’s character out of her late-in-life lethargy. Warm, affecting, encouraging. Despite a few lapses (are post-pot-smoking hunger binges really that funny?), everyone acts like grown-ups and it’s nice to spend time with characters who don’t make me cringe. As with most every movie we’ve seen this year, the performers are all appealing and make the material they play shine brighter.

True Stories (dir: David Byrne, 1986). An art-student type vanity project by Byrne that doesn’t have a proper story, but that’s also not the point. IMDB says there are 50 sets of twins in the movie. Why? Who knows? They’re just there, the way the Talking Heads songs are there, the way the preacher is ranting on SubGenius themes, the way David Byrne stiffly narrates a day in the life of a small Texas town and its amusing small-town characters but never, I think, makes mean or mocking fun of them. He seems to simply enjoy them as they are. I enjoyed the movie’s oddball stance and easygoing pace. John Goodman, in one of his earliest roles, is there with his screen persona fully-formed and grounds the movie with his heart and vulnerability. And, God, but “Wild, Wild Life” is a fun number.

A Serious Man (dirs: Ethan and Joel Coen, 2006). Larry Gopnik is a nice man, but not a serious man, in the sense that his Jewish community in the Minneapolis suburbs would recognize. And when the trials of Job start assaulting him, he has no idea what to do or where to go for help. No blood, no gangsters, over the top in all the right ways, funny, fantastic period detail (the mid- to late-Sixties), anchored to a fine lead performance by Michael Stuhlbarg. The Coens never explain everything in their movies so there is usually something unresolved at its center. I like having some undefined spaces in a story.

Love & Mercy (dir: Bill Pohlad, 2014). Because we had seen The Wrecking Crew documentary a few weeks before, I got a kick seeing them portrayed onscreen in several scenes where Brian Wilson is crafting songs for the next Beach Boys album; for me, these scenes were the most fun of the entire movie. Paul Dano is incredible as the young, strung-out Brian Wilson who finds himself as isolated from the people around him as his 40-year-old strung-out self is under the care of a really creepy therapist. I never really bought John Cusack as the older Wilson. All of the “that can’t be true” moments I experienced seem to have mostly happened as depicted onscreen. Wow.

Welcome to Me (dir: Shira Piven, 2015) Kirsten Wiig is terribly appealing as an unbalanced young woman who wins the lottery, stops taking her meds, and uses her winnings to stage her own Oprah-style show, dispensing bad advice and settling scores with everyone who she felt ever wronged her, from the second grade on up. The movie has the guts to take that premise to its logical conclusion and Wiig goes with it, as her at-first quirkily adorable character sinks into darker places. Hell is inside us and we take it with us wherever we go. This was a movie where, as I watched, I mentally charted the by-the-book plot points, reversals, higher stakes, final push, etc. An OK movie – not bad but not great.

Philomena (dir: Stephen Frears, 2013). We were on a Steve Coogan kick after enjoying The Trip and especially after falling in love with his TV series Saxondale (2006-07). We’d missed this one on theatrical release. Philomena no doubt follows the same screenplay template as many of the other movies on this list, but I found the performers so appealing, the story so sad, and the anger so fresh, I didn’t notice. The movie tweaked the real-life story, of course, but the bones are there. Coogan and Dench make a good team. Worth your time.

Still Alice (dir: Richard Glatzer, Wash Westmoreland, 2014). I remember seeing a TV movie decades ago with Richard Kiley and Joanne Woodward, where Woodward’s character, a poet, is afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease and begins slowly falling apart while her husband bewilderedly tries to understand and cope with the loss of his wife. I’ve also just described the broad outline of Still Alice, which sports a fantastic performance by Julianne Moore, and which features a sequence from the novel that had me on the edge of my seat. Aside from those assets, though, I can’t say this movie said anything more to me than that decades-old one did. It’s gorgeously filmed, and themes of connection/disconnection are always poignant. I choked up at the end when Alec Baldwin, as the husband, talks to their daughter; it’s probably the only time I’ve seen Baldwin that vulnerable and it got my attention and past my defenses.

Vertigo (dir: Alfred Hitchcock, 1958). I backed a Kickstarter campaign for new seats at the Carolina Theatre, and one of the rewards was a backers-only showing of this movie with our backsides in the new comfy chairs. (Nice and cushy but they don’t breathe after about 90 minutes.) It had been decades since I’d seen Vertigo, and watching it on the big screen was glorious – it enhanced the richness of the colors, the swell of the music. The movie has a tone and pace unlike any other Hollywood product of the time, even other Hitchcock movies of the time. I kept trying to squeeze it into a noir box and it resolutely wouldn’t go; it was too brightly lit and beautiful looking (those shots of San Francisco!) to be noir. But its storytelling is less about murder than it is mystery, mood, and tone poem. So many motifs (time, memory, reflections, the abuse of women by men) criss-cross the movie like webbing that its creepiness – especially Scottie’s obsessive remaking of Judy – is hard to shake. Yes, it’s dated, but it has a lingering power and gnawing aftereffect that few movies have.

Currently reading: WE ALL HEAR STORIES IN THE DARK by ROBERT SHEARMAN 📚 Knowing that I’d take on a challenge to read only books I own in the first months of 2026, I bought as a Christmas present for myself this set of books off of Amazon. I’m reading one or two stories a day and they’re delicious.

I’ve always tended to follow the poet and critic Randall Jarrell’s advice – “Read at whim! Read at whim!” I draw in books from local new and used bookstores, little free libraries, Amazon, Libby, Hoopla, and one of the few browser extensions I pay for (doesn’t work in Safari, sadly) Library Extension.

But I was caught by a reading project of Booktuber Michael K. Vaughan who challenged himself to read 500 books he already owns before buying any new ones. He tracks his progress via weekly reading reports and, after 2 years, I think, is now up to the 320s range.

No, I don’t have 500 books, but I do live in an apartment with limited space and one bookshelf.* When we moved, I kept only books that had been signed to me by author-friends, that had sentimental value, or that I knew I could not purchase easily via Amazon.

[* I actually do have a second bookshelf devoted to my graphic novel collection, but it’s out in the corridor of our floor.]

But more books have accrued over time, he wrote, passively, and I have been dragging my feet on getting through them. So while Vaughan’s project is not about reading at whim, per se, it did appeal to my whimsy. So I will instead read at whim among only the books I own, keep the ones I really like, and discard the rest.

A few ground rules for myself:

[* Vaughan reads mostly SF, fantasy, old pulp novels, and comics, though he does read the occasional classic now and then.]

How many books are we talking here? I have no idea; that’s why I’m bounding the project via the calendar rather than with any hard numbers. I won’t get through all my unread books by the end of March, but if I’m chafing to read things outside of my little pile, then I can call however many I did a Win. I can always take up the challenge again later.

When will I do all this reading? With my morning coffee in my rocking chair. And in the evening before bedtime.

Am I a fast reader? When I’m plowing through a book, like the New Bern history book I read recently, I try to read 50 pages a day, more or less. I have the time to do that now, and that number of pages means I can get through most books in a week. Fifty pages a day also keeps details, characters, events, etc. fresh in my short-term memory, and that makes the experience more pleasant for me.

Is this my idea of fun? Oh, yes!

Finished reading: New Bern History 101 by Edward Barnes Ellis 📚 Purchased from Mitchell Hardware during a Christmas stay in New Bern. Of the two popular history books on the town, this was the more substantial in terms of names, dates, and stories on the city’s colonial, Revolutionary, and Civil War history, along with the devastating 1922 fire that swept the city. It also includes extra chapters where the author both dumps his reporter’s notebook and provides key historical documents. I learned a lot but … in retrospect, I probably would have enjoyed the other book more, as it had shorter chapters, more pictures, and looked like more of a fun souvenir while telling more of the town’s quirky stories, like the one about the Taylor Sisters, who aren’t mentioned at all in the Ellis book.

Finished reading: Where Do Comedians Go When They Die? by Milton Jones 📚 A fictionalized memoir of sorts by British standup comedian Milton Jones. The narrator’s reminiscences let Jones ruminate on his craft, his colleagues, his audiences, his agents, and the emotionally brutal pasting a comic runs the risk of taking every time he goes to work. Not a great novel, but if you skim the ludicrous interludes where the narrator is held in a Chinese jail cell, you’ll pick up hard-won details of a comic’s life and art.

A recording from my iPhone’s Voice app from an after-supper walk in June. Rosehill Avenue features a large, high canopy of trees and the sound of the cicadas, tree frogs, etc. This was an experience I wanted to remember. (1m 37s)

I have all three of the collections, but Volume III 📚 is the first I (mostly) read most of. I read this ebook mainly because my backlit Kindle provided the only readable light in our Airbnb. I also felt a grim duty to sample these literary Christmas offerings of the ages and see what if any Christmas spirit they would move in me.

As with all Delphi’s ebooks, these are public domain texts, mostly clean of scanning errors but with a few stories indifferently proofed from the scans. The ebook contains 18 pieces on Christmas themes or that have Christmas as a setting, arranged roughly chronologically and covering a wide range of authors – from the Victorians to a pair of anodyne holiday quatrains by H.P. Lovecraft (!). Alas, the quality range is narrower and, even within that tighter band, wildly variable.

The ebook’s main novelty for me was its collection of curiosities: an overwritten paean to the Pilgrims by Harriet Beecher Stowe (“The First Christmas of New England”) and a group effort (“Message from the Sea”) from 1860 by Charles Dickens and five other writers; the latter is near-interminable in its coincidences, melodramatic situations, over the top stagey characters, and annoyingly verbose omniscient voice. As this group effort is the first story in the collection, one learns from it the valuable art of skimming that will get one through the rest of the book. (Does a novella have five parts? Start at part four.)

Among the standout stories for me: Beatrix Potter’s famous “The Tailor of Gloucester.” Anthony Trollope’s “Christmas Day at Kirkby Cottage” is a smoothly written Christmas trifle of young lovers and misunderstandings, and M.E. Braddon’s “The Christmas Hirelings” is pure sentimental Victorian treacle and all the better for it. Edgar Wallace contributes two smartly done pulp stories, while M.R. James takes the book’s quality prize with two of his unsettling ghost stories, “Lost Hearts” and “The Story of a Disappearance and an Appearance.”

The oddest, most provocative story was Bret Harte’s “The Haunted Man,” subtitled

A CHRISTMAS STORY.

BY CH — R — S D — CK — NS.

In it, a “Haunted Man” is plagued by a Ghost of Christmas Past and is mightily unimpressed by the spirit’s theatrics. The story’s voice and dialog viciously satirize Dickens’ style and his well-known tale:

Again the Goblin flew away with the unfortunate man, and from a strange roaring below them he judged they were above the ocean. A ship hove in sight, and the Goblin stayed its flight. “Look,” he said, squeezing his companion’s arm.

The Haunted Man yawned. “Don’t you think, Charles, you’re rather running this thing into the ground? Of course it’s very moral and instructive, and all that. But ain’t there a little too much pantomime about it? Come now!”

Harte’s “The Haunted Man” and Ambrose Bierce’s cynical “Christmas and the New Year” splash ice water into the face of readers wanting Christmas cheer and comfort. They were bracing antidotes to the other stocking stuffers.

From the New York Times article “Canadian Linguists Rise Up Against the Letter ‘S’”:

In an informal survey this year, Canadians were asked to choose a word of the year. The winner? “Maplewashing,” or the practice (properly spelled the Canadian way, of course) of making something appear more Canadian than it actually is, especially in the context of marketing products for sale to Canadians.

I was bored one evening and applied the Adbreak mod to my Kindle Oasis (10th generation). I was helped along by Dammit Jeff’s video and step-by-step instructions on the Kindle Modding wiki.

Jailbreaking devices like the Kindle are a popular pastime for folks. Getting past Amazon’s defenses allows intrepid users to customize layouts, fonts, UI, load e-books of different formats, change almost every aspect of the device’s function, etc. and add extra programs like simple games or even disabling ads.

I performed a jailbreak on my Kindle Touch back in 2012 so I could load up custom screensavers that delighted me. After a while, Amazon issued an update that broke the jailbreak and I never bothered doing it again.

Dammit Jeff pointed out some interesting apps like KindleForge and KOReader that could be installed,

KOReader was more interesting, as it promised the ability to read many more ebook formats, flow PDF text to make those files more readable, adjust the fonts and sizes of almost every aspect of the UI to your liking. and that’s great – if you want to spend a lot of time fiddling instead of reading.

Also, very few of the many apps available for download via KindleForge seemed worth spending my time on. Do I really need a Tetris clone on my Kindle? No. No, I do not.

So I backed out of the jailbreak and reset my Kindle. I felt more comfortable almost immediately.

Lord knows the Kindle is not perfect. It is a deliberately dumbed-down device with few customizations available apart from loading fonts (Hyperlegible is a good one), a so-so attitude to leading and kerning, etc. As Jason Snell often observes in his Kindle reviews, Amazon could do so much better if it cared to.

But for me, for now, my lowly Kindle Oasis (now discontinued) is fine. It’s fine. It meets my low expectations, the battery still holds a charge, and I can carry 100+ books in my hand wherever I go.

Today’s lesson: Kindles come and go. It’s the books that delight.

Our summer trip to Toronto included a stop at the wonderful McMichael Canadian Art Collection, which featured a great exhibition of First Nations, Inuit, and immigrant art plus a large permanent Group of Seven collection.

Of the landscapes that were on display, the colors and design of Tom Thomson’s landscapes grabbed me. But what has grabbed the public imagination even more than his paintings and sketches are the circumstances surrounding his death and burial(s) (yes, burials). There’s even a whole Wikipedia page on his death and the curious details around it.

Thomson died before the formation of the Group of Seven. Of all the artists from that time, Thomson seems the most singular, remote and unknowable. He preferred the outdoors over the city. He died young with his life and thoughts on art barely documented. All we have left are his paintings and the reminiscences of those who knew him.

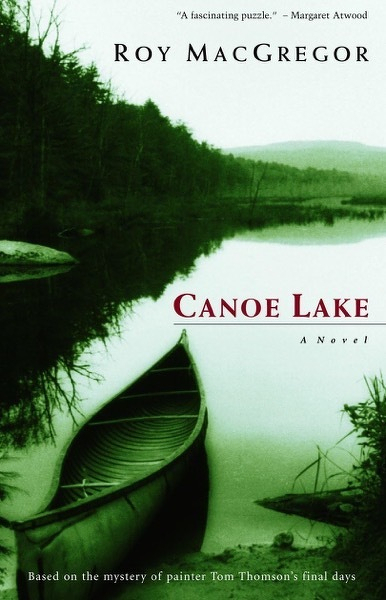

So, interested in Thomson’s story, I picked up two books at the McMichael gift shop (art museum gift shops are the best): a novel, Canoe Lake by Roy MacGregor, and a play, Tom Thompson: On the Threshold of Magic by Barry Brodie.

In Canoe Lake, Eleanor, a young woman from Philadelphia, searches in rural Ontario for her birth mother. Her questions kick off memories in Russell, an old-timer in the village living in a residential hotel, and his friend and unrequited love Jenny, now a spinster recluse but who at one time was going to marry a visiting artist named Tom Thomson. Eleanor’s detective work digging up secrets some people want kept jostles against Russell’s memories of Jenny and Tom, and of course, those worlds will collide in Canoe Lake, the site of Thomson’s death.

It’s a terrific novel, very well done, with depth and great textures, and a sensitivity for its characters, especially the hapless Russell. Definitely worth a re-read.

In his Author’s Note, MacGregor reveals his long fascination with the facts and mysteries surrounding Thomson’s death and MacGregor’s own distant family connection to it. The novel drapes a fiction over the bones of his research, though you can feel MacGregor really savoring the conversations of Thomson’s friends as they examine his body recovered after six or seven days in Canoe Lake, and speculate on the unusual gash on his temple and the fishing line tangled – or wrapped? – around his ankle.

MacGregor returned to the subject later with a non-fiction account of the incident and the times, Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him. The Author’s Note is a précis, I think, for this fuller treatment.

Tom Thomson: On the Threshold of Magic by Barry Brodie is a poetic play with Thomson narrating his inner journey from young man to artist to his afterlife, with all the characters in trembling awe of his artistic vision. Over half of this slim book is in fact devoted to the play’s writing and initial staging, and the back-stage stuff is honestly the most interesting part.

NB: Thomson’s studio now sits on the McMichael grounds.

Note: I found this draft in a folder of old documents I’m clearing out. I have no idea when I wrote it, but between 2018 and 2022 is my best guess. I saw it was not on the blog, so am finally posting it here.

Saying “thank you” is one of the great civilized acts we do in daily life. It makes our social interactions with clerks, vendors, waitstaff, co-workers, friends, family – nearly anyone we come into contact with during our day – a little more pleasant.

“Thank you” marks the end of a transaction. We have concluded our business and I want to express my gratitude for your part in it. “Amen” is not too dissimilar in action and meaning.

But when it comes to saying “thank you” in email … aye, there’s the rub. Is it courteous to send a one-liner “thank you” email or are we burdening the recipient with yet another task and decision we have forced them to make?

My friend Bob calls these one-liners “closing the niceness loop.” We’re so obsessed with appearing “nice” that we waste our time and our recipient’s time with a one-liner email that did not need to be sent.

And if there are multiple recipients of the email on the CC line: heaven help them. Their inboxes are now filling up with one-line “thank you” emails followed by the obligatory replies of “you’re welcome” or “sure.”

Delete, delete, delete.

Fast Company, in an article on bad email habits, also condemns the puny one-liner:

Replying to an email with “Thanks” or “OK” does not advance the conversation in any way. “You don’t have to answer every email,” says Duncan, who takes a moment to analyze our email conversation. When I asked Duncan if she was free at 3 p.m. to chat, she replies yes and sent me her phone number.

“A lot of people would have replied ‘Okay, great, talk to you then’” says Duncan – an unnecessary email that simply clogs up someone’s inbox and doesn’t contribute anything to the conversation. To avoid being the victim of one-liner emails, feel free to add “no reply necessary” at the top of an email if you don’t anticipate a response.

Nick Bilton, in the NY Times Bit Blog:

Don’t these people realize that they’re wasting your time?

Of course, some people might think me the rude one for not appreciating life’s little courtesies. But many social norms just don’t make sense to people drowning in digital communication.

Take the “thank you” message. Daniel Post Senning, a great-great-grandson of Emily Post and a co-author of the 18th edition of Emily Post’s Etiquette, asked: “At what point does appreciation and showing appreciation outweigh the cost?”

That said, he added, “it gives the impression that digital natives can’t be bothered to nurture relationships, and there’s balance to be found.”

I find the one-liner thank-you a hard habit to break on our cohousing community mailing lists. We’re all volunteers in the effort so saying thank-you seems like a (cringe) nice thing to do to show appreciation. But when I look at a 15-message-long thread that contains 10-12 “thank-yous,” I cringe there too.

I favor not sending the one-liner. Those replies don’t advance the conversation, and I think they annoy all the other recipients who are eavesdropping on the thread and don’t care anyway. (In other words: it annoys me when I’m on the CC line of those threads. At some point, I mute the thread.)

Also, it’s likely I’ll see the person in real time or email with them on another topic; if a thank-you is indicated, there are plenty of opportunities to fold it in with another message.

However, there is a type of one-liner email I always send. When I’ve been assigned a task via email, I will reply with a single word – “Done” – to signal that the task has been completed. Since we’re all keeping records of our work in our email, I want everyone else’s inbox to have a record of what I did and when.

Thank you for reading.

Every Christmas, my mother gives me a subscription to Our State magazine, which, as the subtitle says, is dedicated to “celebrating North Carolina.” I like browsing each issue to find some new or unusual places to visit for a day trip or long weekend. Although I’m a native North Carolinian, there’s lots I don’t know about the state.

This year’s Christmas-themed issue delighted me more than usual. In addition to the recipes and events – Peanut Butter Cup Cookies! Christmas Flotillas! – are some really well-reported (if occasionally overwritten) articles on bits of hyperlocal history, culture, and the passing scene.

Brief excerpts from some of my favorite articles:

Christmas on Portsmouth Island - More than 50 years after the last residents of Portsmouth Island moved away, a descendant of the once-busy shipping village decks the halls in their honor.

His father — a carpenter and commercial fisherman who worshiped during homecomings in this same church — passed away about six months prior. In this moment, the loss deepens Gilgo’s connection to this place and the meaning of the Christmas season. Satisfied with the job, he turns to leave, his work now done. He may be one of only a few handfuls of people who ever see these decorations, and that is enough.

Resilience in the Ebersole Holly Garden - Once left to the weeds, a world-class holly collection in Pinehurst is thriving again, thanks to the determination of those who believe in a second season.

Most people think they can identify a holly. “You imagine that evergreen, Christmas-tree shaped bush at the corner of your house,” Bunch says.

To expand that notion, he takes visitors over to one of his favorite spots in the Ebersole Holly Garden, a section filled with massive trees, some boasting 40-foot-tall canopies. Bunch encourages them to look up. “These huge, beautiful hollies have white-and-gray bark, different from any other trees — a stark contrast to our native pines,” he says. “To get underneath them is a different experience than from looking straight on to the holly bush in your yard.”

Old Christmas in Rodanthe - For more than 200 years, villagers in the Outer Banks community have celebrated Christmas on their own terms.

As the story goes, during the [[Battle of Culloden]], a nonfatal arrow struck the 12-year-old Scottish drummer, Donald McDonald, in the left shoulder. After his recovery, he set sail to the New World, drum in tow. During the voyage, McDonald fell overboard during a storm and swam to shore using the drum as a life preserver. He arrived at the place where he’d spend the rest of his life: Rodanthe.

… The drum is folklore made material. A symbol of persistence and resistance, it bridges past and present. According to legend, decades had passed when news reached Hatteras Island that England had, in 1752, adopted the Gregorian calendar that changed Christmas from January 6 or 7 to December 25. Committed to their ways, the village of Rodanthe refused to go along with the change and continued celebrating Jesus’s birth when and how they always had.

North Carolina’s Santa School - Before the beard and belly laugh, becoming the Man in Red requires a little magic — and plenty of training — in Charlotte, where Santas go to earn their ho-ho-ho. A wonderful piece by Daniel Wallace.

On offer this weekend is a rare opportunity for Santas from all over the state and beyond to watch other Santas at work, to study their routines, and, not unlike a child at the mall getting their picture taken with the Man in Red, to ply the old pros with questions of their own, such as, well, “What do you say when they ask you where your reindeer are?” No two Santas have the exact same answer to this question, or to any question for that matter. But you need at least one.

Locopops’ ice cream board

We attended the No Kings rally yesterday at Durham’s Central Park, along with 5,000 to 7,000 other folks. A beautiful sunny, warm day with lots to see. So loud and crowded we could barely hear the speakers, but the vibe was everywhere.

A quote from the Indy Week story linked above:

“Then [[at the time of the previous No Kings rally]], it seemed like it was on the edge. Now, we’ve fallen off the edge. We are falling, free falling. So it’s that imperative, like today, to come together even stronger,” Monpetit said. “Hopefully, coming together like this, we can figure out who we are and what we’re doing together. The more we talk, the better.”

A friend told me of the “Drunk Trump Game”, which is to find on YouTube a speech by the current occupant and then play it at a speed of .5 or .75. To my ear, he doesn’t sound so much drunk as sleepy.

(“Current occupant” is the appellation used by Orange Crate Art, which we have adopted.)

Finished reading: An Old Woman’s Reflections by Peig Sayers 📚

Life on Great Blasket island, three miles off the west coast of Ireland, was hard and cold, with a meager living scratched out from the ground and the sea. Life in the 20th Century was as primitive as it had been in the 18th and 19th. Among other effects of this isolation was the community’s continued reliance on Gaelic to pass along its rich oral tradition of history and folktales. The island never had more than 150 or so inhabitants and was eventually abandoned in 1953.

Oxford University Press published a series of seven books of Great Blasket memoirs and reminiscences. Peig Sayers was hailed as one of the island’s great storytellers. Her book is a collection of transcriptions of stories written down for her by her son, stories she remembered from others’ telling and stories of what happened to herself.

It took a while for me to get into the rhythm of the book; these stories were meant to be told, of course, not written. When she quotes poetry, the words are transcribed into English as lines of unrhymed prose, so there is a natural loss of emotion and power. And I’m sure the music and rhythms of her speech, the way she would tell the story, would make these reminiscences come alive in a way that they don’t on the quiet page.

Still, as descriptions of a time and place long gone, I was fascinated by the details of the lives they led and the characters she knew. Since we can’t recapture the experience of Peig’s storytelling on the page, here’s a description of the effect they had on a neighbor who had actually sat around her fireplace and heard her stories:

Often her thoughts would turn to sad topics; she might tell, for instance, of the bitter day when the body of her son Tom was brought home, his head so battered by the cruel rocks he had fallen on from the cliff that his corpse was not presentable to the public. So Peig, with breaking heart, had gathered her courage together and with motherly hands had stroked and coaxed the damaged skull into shape. ‘It was difficult,’ she would say; and then, with a flick of the shawl she wore, she would invoke the name of the Blessed Virgin, saying ‘Let everyone carry his cross.’ ‘I never heard anything so moving in my life,’ a Kerryman confessed to me, ‘as Peig Sayers reciting a lament of the Virgin Mary for her Son, her face and voice getting more and more sorrowful. I came out of the house and I didn’t know where I was.’

Finished:

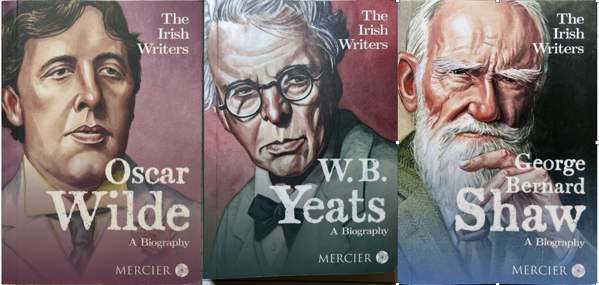

A neat little set of literally mini-biographies – each about 200 pages and about 4"x6" – very easy to hold in the hand. Bought from a newsagent’s across the street from Trinity College in June 2025. Apart from their major works, I knew very little of these authors so these little biographies suited me just fine.

Stray observations:

Of the three, Yeats was most involved with their home country. Part of his vision was to establish a modern Irish literature, written in English, and Ireland continued to be a prime source of his inspiration, even though he spent as much time in England as he did there. Wilde was not concerned with Ireland. Shaw never forgot that he was an Irishman, and like Yeats was a Unionist who believed in Home Rule. But, though much in his thought and writing is Irish, he did not feel the rootedness in Irish history and culture that Yeats felt and nourished. He wanted to reform not Ireland or England, but the world.

Finished reading: Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan 📚

One of the blurbs says “ice cool, self aware, and very funny.” Definitely icy and detached. A witty novel of a young lower-class Irish woman in Hong Kong and her romantic and sexual adventures among higher-class striving junior professionals. The characters are so high-verbal and articulate that you could cut yourself on their casual, lacerating banter. Ava, the narrator, is so detached from her own life and needs that I felt equally distanced; as funny and sparky as she could be, I also wanted to shake her and tell her to grow up. Though that last page is really good: her body finally chooses what her busy mind has denied her. The last of the books I bought in Ireland.

The Chris Ware-designed stamps arrived today! I bought two; one to use, one to keep.

Typical Ware genius of meticulous design and wit in storytelling: “The pane of 20 interconnected stamps shows a bird’s-eye view of a mail carrier’s route through a bustling town. Laid out in 4 rows of 5, the stamps depict the story through the 4 seasons from top-left to bottom-right.”

Just discovered via the New York Times that although I’ve considered myself a Libra all these years, now I’m a Virgo. I’m sure there’s a difference.

Took the morning deliberately slowly, let myself go down various online rabbit holes, and then BAM nonstop activity for 3 hours. I keep wanting to leave my old time management habits behind in retirement, but I don’t think I can.

Did my ankle and knee PT this morning, read another story in the latest First Line literary magazine, and started in on my inbox.

Since my semi-retirement in April and now full retirement, I’ve found that my much-vaunted and hard-fought-for productivity habits have totally unraveled. With no one imposing a deadline on me, I tend to get around to things when I want to do them. Which is, in its own way, very relaxing. I get to things, just not when other people want me to get to them.

I’m unsubscribing from some newsletters, or moving them to Readwise Reader app. I usually delete a lot of things that arrive daily, which are reminders from FollowUpThen or ads from local businesses I want to stay aware of.

On a day like today, where I have 50+ emails in the box, I like to sit and just plow through the inbox from top to bottom, put stuff in Google Tasks or Keep or Evernote, and then stop when the inbox is empty or I’m tired of doing it.