Denver, October 2016

Liz presented at the AMWA conference, so I tagged along and cavorted at will. From the mental grab-bag:

- I stayed pretty much in the 16th Street mall area, since we didn’t have a car. That’s OK – plenty to walk to from there, though like most malls, chain stores dominate the landscape.

- We stayed at the downtown Sheraton, the largest hotel in Colorado, we were told. Also, kind of staid. Nothing special here.

- We ate all our evening meals in the Yard House, a sports bar attached to the Sheraton. Loud and expensive, it nonetheless served excellent food and we were never disappointed. (I favored the Cobb salad and chicken tortilla soup.) Liz also liked their sour beer. We never could figure out what the phrase “yard house” meant.

- Thank God for the Peet’s Coffee just off the lobby – a life-giving Americano started my busy days.

- I spent almost my entire travel budget just buying meals on this trip. I settled on two meals for the day, with the occasional protein bar as a pick me up, and that did me fine.

- The Tattered Cover Book Shop is housed in an old railway warehouse and is a marvelous place to browse. City Stacks is a cozier, brighter bookshop where I had a very good peppermint tea and browsed the art books.

- Denver struck Liz as heavily male: young men in groups of three and more, bushy beards, tattoos, ear gauges. Lots of young men. Joe told us that Denver is in a tech boom and can’t hire programmers fast enough; that also answered the question of how all these young people could afford to hang out in this expensive area. Joe also said that “LoDo” (Lower Downtown) has become so infested with packs of guys and bros that the area is now called “BroDo.”

- The History Colorado Center had the Awkward Family Photos show alongside its own photos of turn of the 20th century Denver and Colorado. Interesting to note the similarities, differences, and reactions between the two shows. I did laugh a lot at the Awkward Family Photos, but I’d love to have a book of the older photos and just stare at them for long periods of time.

- Always take free walking tours. The free downtown tour took two hours and showed me places, like Larimer Square and the Blue Bear, that I’d overlooked wandering on my own.

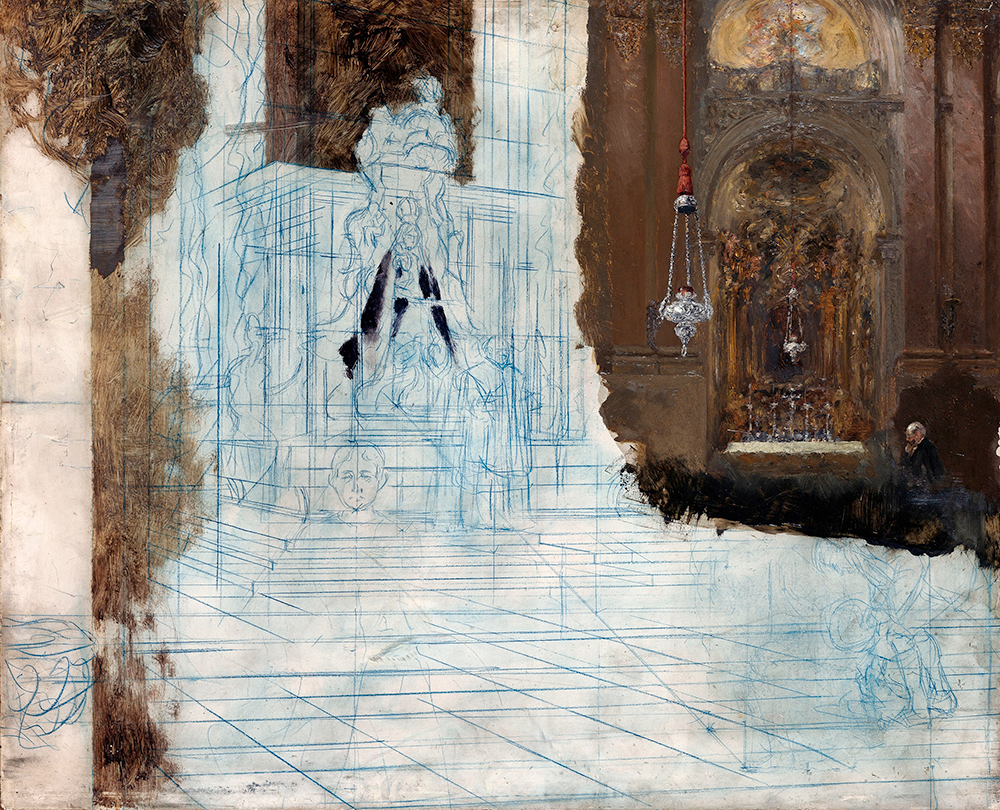

- I spent a few hours in the Denver Art Museum. With exhibits in two buildings spread among 11 floors, I couldn’t hope to see it all. And besides, after a couple hours, I’m museum’d out. I went to the Glory of Venice exhibit, wished for more of the poster art exhibit, looked at the English and American art collections, the Western and Native American collections, and called it a day. Good for the soul.

- I walked miles and miles every day, and came back 1.5 pounds lighter.

- Was it the altitude or the desert environment that aggravated my allergies? I thought I was coming down with another cold before I hit on the right allergy meds that let me sleep without dying of post-nasal drip strangulation. Also: water (and lots of it), chapstick, and sunscreen!

- We totally missed the bizarre murals that decorate the Denver Airport and apparently form an apocalyptic story. Search on “Denver Airport murals” and a door opens to a new room of the internet that you didn’t know was there.

- We had a wonderful dinner and evening catching up with our friends Heather and Joe, the highlight for me of the trip.