Furlough Diary - Day 10

I work for a government contractor, and we were sent home at 11:30am on Tuesday, Oct. 1. The company (rather generously, believe it or not) covered everyone's hours that week. This week, we're taking mandatory vacation. No indication yet what next week's plan is.

I’ve not been that disturbed. Oh, I’ll pay for this time off, no question. I will wind up owing the company hours or days, or I won’t have any vacation pay over Christmas. But for now, I am quite simply enjoying my time. I also know that this is a temporary problem, unlike being unemployed (which I have endured). I have the feeling I’ll be back at work soon enough.

(On a related note: I avoid much of the news surrounding the shutdown. I can't do anything about the situation, apart from write to my representatives, which I did. So I'm letting them handle it while I get on with my life.)

Last week, I focused on creating a set of emails for the neighborhood association's upcoming community meeting. I devised a set of twice-weekly emails, wrote them all, sequenced them, and then set up email reminders for myself. My system will remind me when it's time to post an email to the neighborhood listserv and then I'll take care of it. It took way longer to do that than I thought it would, mainly because I was procrastinating on writing 8-10 emails. But once I got started, I was able to push through and get them done.

Which then left the problem of what to do with acres of unscheduled time. Is that a problem? It doesn't have to be. But I've discovered over the years that if I don't have a project or some structure to my day, I do go to pot pretty quickly.

This would be a golden time to update my LinkedIn profile. I could also call that entrepreneurial non-profit and set up an appointment to talk to them about starting their program. Right now, all my eggs are in one employer's basket; it might be better for me to start my own endeavor that puts me more in control. I've written the email to the non-profit, but I've not sent it yet. I don't know why.

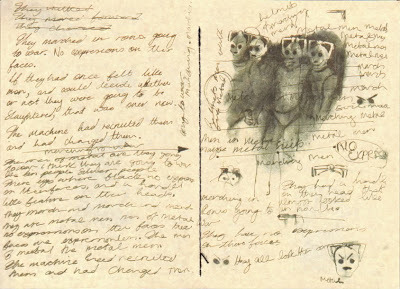

I have a creative project I had set aside so I could focus on the neighborhood project; I'm trying to not chase two rabbits anymore. I've been ramping up the research and writing on that project. I find the mornings are the best time for me to write and edit, or sometimes later in the evening. Afternoons are for housekeeping, laundry, desk cleaning, reading, and, if possible, a 20-minute nap at 2 or 3 pm.

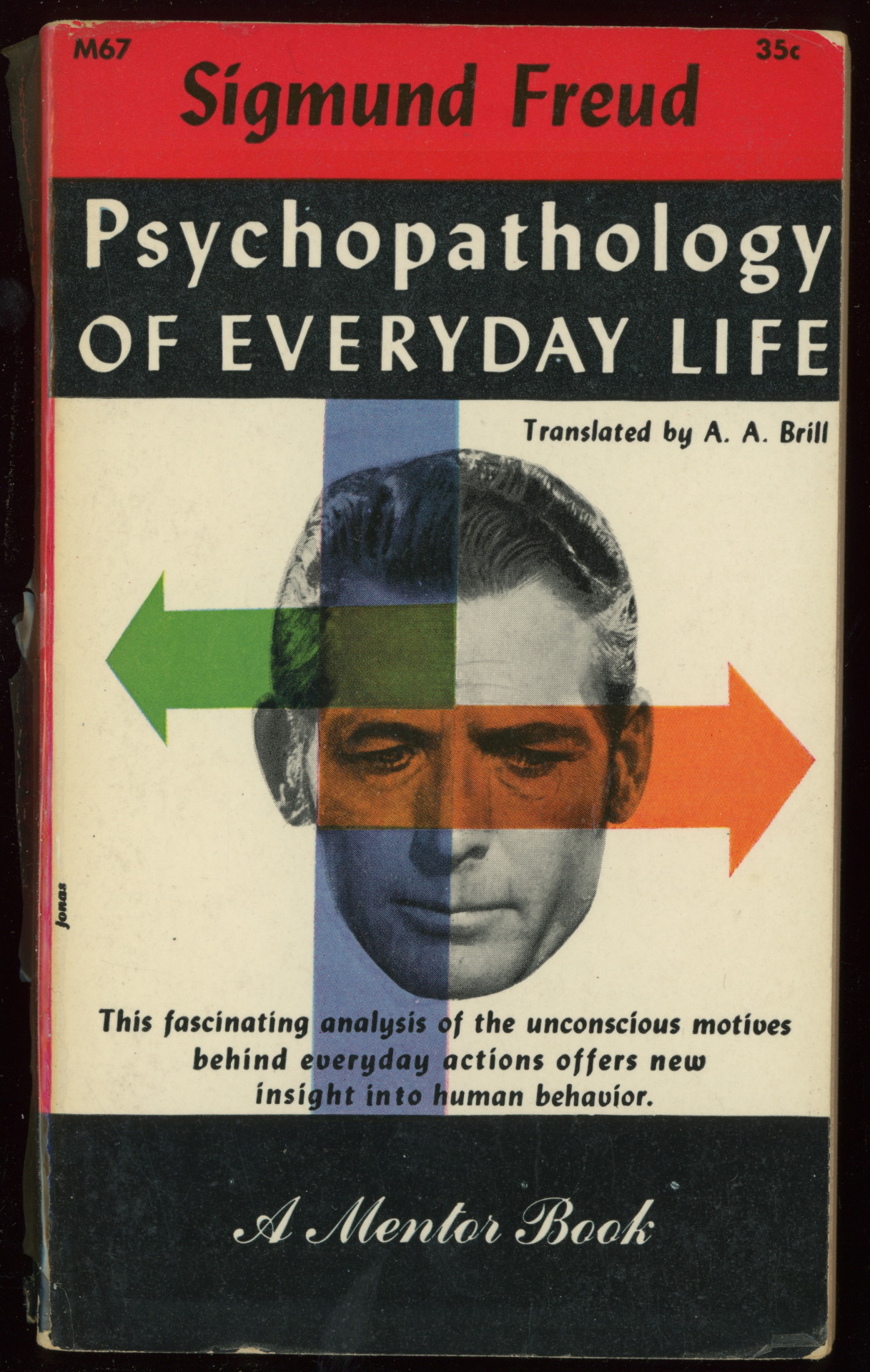

I also charged through a few motivational books by the coach Steve Chandler on my Kindle. I'll probably write them up here sometime. I'm reading a third book of his to see if the same themes recur.

I've also taken the opportunity to meet friends and acquaintances for coffee, without feeling the need to hustle back to the office. Running errands has also been less stressful. I do like to leave the house at least once a day, even if it's just to put gas in the car, otherwise I get cabin fever.

The weather lately has been cool, due to Tropical Storm Karen, so I set up my office on our screened-in back porch. It was lovely. Whenever my eyes or shoulders got tired, I could set the MacBook or Kindle aside and look out at the trees and the bird-feeders and just relax. It's so odd to have so much less thinking going on in my mind. The job takes the best hours of one's day, and the days are filled with a thousand decisions related to problem-solving, writing emails, deciding where to go for lunch, returning phone calls, etc. With less on my plate, with fewer problems to solve, there's subsequently less on my mind and my god is it peaceful.

Tomorrow is my banjo lesson in the morning. I will shop at the grocery after to get the food I'll make for supper tomorrow night. And I'll have time to write, read, have a nap. It's not like floating down the Mississippi on a raft, but for me, it's pretty good.