[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mj5IV23g-fE&hl=en&fs=1&w=300&h=242]

Thanks to the glory of Netflix, Liz and I saw this documentary that I can assure you never visited the Carolina Theatre. It's a bio-doc on the writer Harlan Ellison, 72 years old at the time of the movie's release in 2007, and covers an impressive sweep of his life, with samples of him reading from his stories, talking heads quotes from friends and other writers about his influence and the impression he's made on their lives, and various NSFW-language interviews that evoke the man's history, philosophy, irritations, annoyances, and, now and then, joys. (The YouTube video here is from the movie; it's HE in his most typical mode of full-flow righteous anger--well-deserved, in this case.)

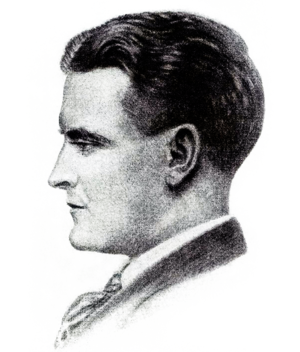

I was introduced to HE as a sophomore in high school and didn't look back for nearly 15 years; his personality and writing were vivid, electrifying, throat-grabbing--uncompromising, is the word that leaps to mind. Uncompromising to the point of lunacy, sometimes, but all in the name of dignity, self-respect, and justice, which for HE are paramount virtues.

"Dreams with Sharp Teeth" was a real test, as Liz had never experienced Harlan and was put off by his abrasive and, it must be said, obnoxiously show-offy personality. But she said she grew to like him better as the movie went on; you see the grit, energy, anger and just plain orneriness (an old-fashioned word that Harlan would love) that took a bullied little kid from Painesville, OH (a metaphorical town name, if ever there was one) to Los Angeles and success, of a sort. The movie confronts the fact that, although his writing has always been admired by his peers and lauded by fans, his career never really took off. His labor in the vineyards of genre fiction, teleplays, and short stories won him many writers' awards, but not mainstream success.

The documentary recognizes the respect that is paid to his longevity and his highest writing achievements--especially some of his most important short stories from the 1960's, such as "Repent Harlequin, Said the Ticktockman" and "I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream." But he still remains a marginal literary figure, it seems to me, a miniaturist in a culture that likes The Big Novel, the province of a dedicated few. His legacy, in addition to his thousands of stories and awards, may be more in the writers he has inspired who've gone on to produce Babylon5, the revamped Battlestar Galactica, and other TV series, or had more commercially successful writing careers themselves (such as Dan Simmons and Neil Gaiman, who pay tribute to HE).

As Gaiman says in the interviews, HE's greatest creative act has been this character called "Harlan Ellison." Partly sincere, partly schtick, with a freakish a memory for cultural and historical details, a fast-talking patter, and in-your-face energy--an electrical storm front on legs--driven by a hair-trigger temper and a determination to prove he's better and smarter than the bullies around him.

He says, in a poignant reflection, that being beaten up every day by bullies makes you an outsider. I think that, in many ways, large pieces of him are still hurting and still wants a happy childhood.

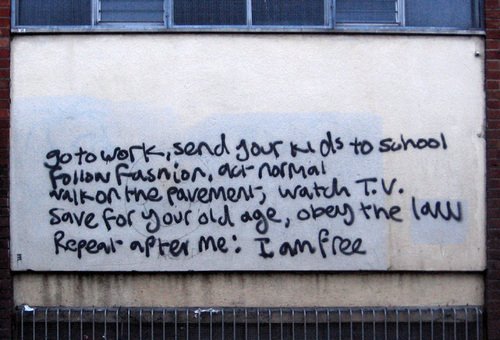

Another legacy of his childhood is that he sees the world as a big bully that shouldn't be let off the hook. In fact, the bully should be shamed, kicked where it hurts, and his nose should be rubbed in it. ("Revenge is a good thing," he says in a 1981 TV interview.) It powered his writing and his political and civil rights activism, his numerous lawsuits against studios and networks, and made him a fiercely loyal friend and ally. But it also meant he couldn't pick and choose his battles because everything--from a Writers Guild contract to the wrong brand of yogurt at the grocery store--demands a shouting confrontation, and if you cross him, then get ready for screaming phone calls.

While he never got to be one of the writers of great movies, as I think he dearly wished to be, it's hard to imagine him being happy on a movie set. To have the sort of control he wants, he'd have to do what his acolytes have done: become the producer and helm the entire enterprise. But that would mean he'd have to be the boss, and I'm guessing he'd not enjoy that role. He considers writing his holy chore, not producing or directing. Although I think he'd love meeting and kibitzing with the actors (his life's wealth could be said to be the devoted friendships he's gained of rich and famous people), he'd be driven to mania and a rusty chain saw by the thousand compromises and trade-offs that are a major movie production.

And also, he's always been an outsider; to be a producer/director would mean having to work inside the system, and he couldn't flatter and cajole the suits whose primary concerns are the budget and the schedule, not the story. HE knows his confrontations and lawsuits have poisoned the studios and investors against him and made him virtually unemployable except by a few younger-generation writer/producers who see him as a mentor who inspired them when they were teenagers. He says he has accepted that condition--though it's hard to be sure. Regret and disappointment are other major themes in his work.

The movie is a wonderful hagiography of Ellison (much better than the similar "The Mindscape of Alan Moore" in 2005) though it does assume that he's loved by his fellow writers, which isn't always the case. "The Last Dangerous Visions" issue is lightly touched on and then set aside. There has been some criticism of the movie because none of his enemies are interviewed--HE reportedly told the director, Erik Nelson, that he's known by his impressive enemies list and they should have a hearing in the documentary--but Nelson replied that HE was his own worst enemy.

I've grown up seeing HE's image in photos and television interviews, and it's poignant to see how he has aged. The geeky kid in his teens becomes the slim, handsome, dynamic ladies' man in the 1970s and 1980s, and now is a round matzoh ball who looks like Larry "Bud" Melman. The fire is still there, but the heart attacks, surgeries, chronic fatigue syndrome, and other maladies (none of which are described in the documentary) are catching up with him.

I came to HE's writing first via The Glass Teat, which a high school friend introduced me to. For the next 15 or so years, I became an Ellison fanatic, read all the stories, interviews, columns, etc. His last great book of stories, to my mind, is Strange Wine. He's written some remarkable stories afterward--"The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore" was selected for Best American Short Stories 1993--but I've not enjoyed them as much as I did his early work. His art has evolved from pulp genre fiction, to his own brand of fantasy, to, in the last 20 years, a Borgesian lyricism and vision, with non-linear stories that are collages, impressions, prose poems, descriptions of mood and interior states rather than character. That I can't connect to this vision--which eschews the traditional short story and plot props I'm accustomed to--I will take the blame for. As an artist, HE continues to evolve and follow his muse where it leads him; not all of his old fans can do the same.

I was often struck by the fact that HE wrote two or three novels during his years as a pulp writer, but none afterward. I think this was a shame and a missed opportunity. It could be that his inclination was more for the pointed message, the singular effect, the impatient prophet--maybe he had too many things to say--a sprinter, rather than a marathoner. Of course, the screenplays he wrote (such as his famous unproduced screenplay for "I, Robot") also took as much time and measured energy to write as a novel. But I think movies called to him as an artist in a way novels couldn't.

The documentary features television interviews from his heyday in the 1970s and 1980s, and a small tour of his remarkable pop-culture museum of a house, which is stuffed to bursting with books, ephemera, and toys. It struck me as the magical treehouse his 8-year-old self would have wanted to live in, a very safe and cozy Xanadu (complete with secret passageways and pizza) that's retreat and recharging station and probably everything HE would have ever wanted.

It will be odd the day I wake up and hear that Harlan is not part of the landscape. I wonder whether he will see death as a bully or a friend.

Where to start. For the fiction, The Essential Ellison is a good but large and baggy collection; Deathbird Stories is an earlier and more compact volume that contains many of his classics. Dangerous Visions is his groundbreaking SF anthology; I've not read it in decades but still remember some of its stories. His Dream Corridor comics are interesting curios, but not essential.

I daresay that his reputation, like Gore Vidals, may rest on his essays, which are remarkably supple yet all of a piece. It's in these essays (and the introductions to his stories) that the Harlan Ellison voice and "character" were forged, and I can recall more happy moments reading them than I do his fiction. Sleepless Nights in the Procrusteam Bed is the best nice-sized volume that shows his range. The Harlan Ellison Hornbook reprints his 1960s essays and they're all immediate and throat-grabbing. Harlan Ellison's Watching contains his fugitive movie criticism; The Glass Teat and The Other Glass Teat contain his classic dissections of network teevee in the 1960s--truly a snapshot of another era and full of opinions that are still scarily relevant.

In the 1980s, he started a fan club thing called The Harlan Ellison Record Collection, which made available recordings of him reading his work. (This was pre-Internet days, kids -- it was all done by mail and Pony Express.) Listening to him performing (not reading, performing) "Prince Myshkin, or Pass the Relish" and "Waiting for Kadak" are more fun than reading them. I also hugely enjoyed the 60-min interview of his "Loving Reminiscences of the Dying Gasp of the Pulp Era"; he clearly has a great nostalgia for that period of his young manhood, and there are times he can sure sound today like a cranky old man lamenting the good ol' days.

But it's the recordings of his public lectures that are the most entertaining. Of the On The Road series, my friend Scott says that the preferred order would be vol. 2, then 1, then 3.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=f46742bc-7137-4657-bc9d-d33e6bdf0fbe)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=f96c48b6-7a8b-497b-bdba-8def6320f473)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=91d16d64-86e7-457c-b226-6a1f92d31903)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=8b404eb5-dca2-4bf4-8120-5e242045ebb2)