Encounters With an Enlightened Man by Linda Quiring. Of the three books written by Quiring about Sydney Banks, this is probably the best. It misses the freshness of the first two books, which were written in the early 1970s when Banks started sharing his enlightenment experience, but it tells a beginning-middle-end story and paints a more complete picture of the place and time. Of interest mainly to people interested in the history of the Three Principles and Banks’ personal history. I am drafting a bigger post that takes a look at all three books.

Silver Screen Fiend: Learning About Life from an Addiction to Film by Patton Oswalt, read by Patton Oswalt. A memoir by Oswalt of the movies he compulsively watched during his first years in Los Angeles. It’s a story of being in the grip of a mild obsession well-known to those of us with a geeky/nerdy bent. His girlfriend at the time asks him to walk her out to her car from the theatre, and his first, absolutely natural, response is, “But I’ve never seen the start of the next movie and I don’t want to miss it.” Exit one relationship.

Parallel with his obsession is the evolution of his standup, writing, and acting career and how he tries to juggle that with the nightly movies shown at the New Beverly. The most chilling and haunting story to me is of a long-ago standup comrade who imposes on Oswalt for a shot at becoming a star; Oswalt has already become a character of fiction in someone else’s movie. He introduces and returns to the idea of special, sometimes dark, moments that propel one forward in life or work. He wrote this before the death of his first wife, so listening to those passages struck me as especially poignant.

The Correspondence by JD Daniels. A collection of laconic essays and two short stories that originally appeared in The Paris Review. Here’s a passage from a short story:

She’d gone to school for years to study library science. He didn’t see how it could be so complicated. It seemed like a hoax.

All the essays and both stories have that terse, dry flavor; the humor is almost an aftertaste. A rather short book, too – I read one essay or story a night in about 30 mins or so.

Jacob T. Marley by R. William Bennett, read by Simon Vance. Bennett finds a loophole in Dickens’ story to spin a tale with 19th-century flavors, coincidences, and voices. It’s a clever reworking of the original material that exploits unexplored nooks and crannies, though he does get a bit bogged down as the spirits explain the metaphysical mechanics of the afterlife and what is required for Scrooge’s reclamation. Though, if I heard the story right, it’s Marley’s sacrifice that redeems Scrooge rather than Scrooge’s own change of heart. If so, that makes Dickens’ story subservient to Bennett’s, which does not sit well with me.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Capote, read by Michael C. Hall. I had never seen the movie nor read the book so this was new to me. It is very much a book of the 1950s – rather gray and naturalistic, the secondary characters all stagey and one-note – except when Holly explodes into the narrative with unnatural color and life. Holly is clearly the most interesting character and the mysteries surrounding her are the ones I cared about the most. Hall’s reading was fine though I didn’t care for his expression of Holly’s voice. For further reading: an excellent Open Letters Monthly essay compares and contrasts Sally Bowles and Holly Golightly.

Just Keep Going by Jeanette Stokes. Disclaimer: Jeannette is an acquaintance we run into at random cultural events here in Durham. The book is part of her ongoing memoir series; this one focuses on how her relationship to writing, art, and creativity marked key passages of her life. A compact memoir with a good collection of basic advice and resources for the new writer and timely reminders for the experienced one.

Tales of the Batman: Alan Brennert (Comixology). Archie Goodwin had a long career in the comics industry and was a much beloved writer, editor, and mentor. His Batman stories in this volume span the years 1973-2000. They tend to the pulpy and the “well-made.” He also seemed interested in expanding the canvas on which Batman stories could be told; many of the stories delve into character histories and motivations – with lots of exposition – making Batman almost a secondary character.

They’re good meat-and-potatoes Batman stories that color in unnoticed areas of Batman’s universe (who did design the Batarang and Batmobile?). The highlights for me are the six or so Manhunter stories that ran as backup to the main Batman series and that I still remembered from when I was a kid; so glad they’ve been collected at last. Goodwin’s updating of the 1940’s Manhunter character to the cynical modern-day prefigures work that Alan Moore would take to another level a decade or so later. It’s Walt Simonson’s artwork that made these stories instant minor classics.

Alan Brennert has been a successful writer in many media: stories, novels, TV, even the book for a Broadway musical. He only wrote nine stories for DC, his first in 1981 and his last in 2000. Yet they include some of the most interesting takes on the Batman mythos, mixing the pleasure of nostalgia with the character development he used in his scripts and novels. For me, his stories pay the best dividends every time I re-read them. I remember buying these comics back in the day and noticed even then how different his stories were, how he pulled out details or emotional colors that I did not see elsewhere.

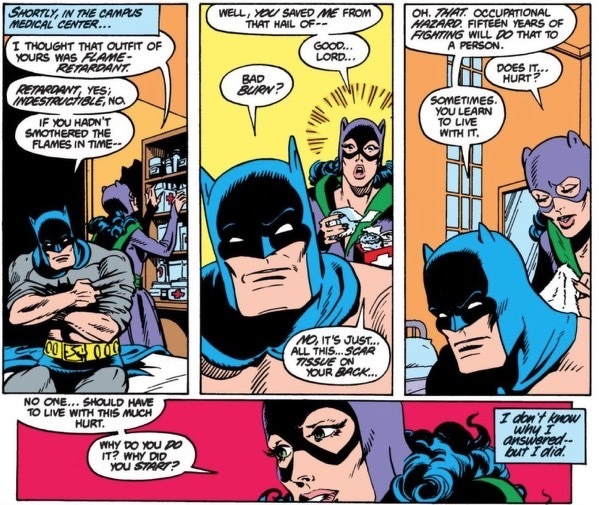

Brennert had a particular fondness (as do I) for the “golden age” or “Earth-2” Batman and my favorite story of his – maybe one of my favorites of all time – is the Earth-2 Batman teaming with Catwoman to hunt down the nefarious Scarecrow (“The Autobiography of Bruce Wayne”). Joe Staton and George Freeman drew the chunky Batman from the ’50s, a style that instantly evokes the light-hearted adventures of that era. But Brennert adds a moment that stops that feeling dead in its tracks.

Batman removes his shirt so Catwoman can attend to his wounds. She gasps at the scar tissue covering his back; it’s key that we see only her horrified reaction and Batman’s stoic response. That scar-tissue detail is so unexpected in the context of a “retro” Batman story, yet such a common-sense detail considering his life of fighting, that I am still amazed Brennert was the first to conceive of and use it. It’s a telling detail that’s now accepted as a given and enshrined in the movies.

Brennert had that freedom of approach – perhaps from his work in other media – to give his characters time to breathe amid the action and feel the weight of emotional moments. That’s not something you see in comics very much, and it’s always appreciated when it happens.

Updated on 2026-01-30