Purchased from The Odd Book, a really terrific used bookstore two streets back off the main drag of Wolfville, NS. I spent a delightful couple of hours browsing the small but packed alleys of shelves. Fantastic collection of Nova Scotian history and literature. 📚

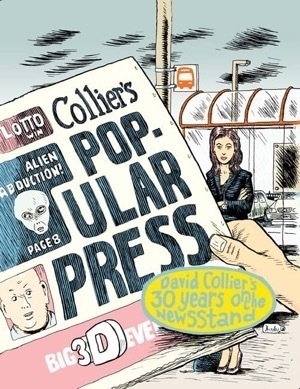

Collier’s Popular Press: David Collier’s 30 Years on the Newsstand by David Collier (2011)

A generously sized collection of the Canadian alternative cartoonist’s fugitive journalism, comics, single-panel cartoons, and sketches for all manner of Canadian newspapers. The comics journalist Jeet Heer’s introduction praises Collier’s craft and his love of homey detail, which are evident in his wonderful landscape drawings that lead off the book, his comics-based diaries, and his own written reminiscences, including a pilgrimage with Pat Moriarty to the house George Herriman lived in.

Collier’s self-portraits, line detail and cross-hatching, and stories where he casts himself as an overly self-conscious overthinking nebbish struck me as very Robert Crumb-y, but without that artist’s graphic skill, emotional intensity, and attention-grabbing sense of danger. I mean, Collier is Canadian, after all. So the collection as a whole is gentle, low-wattage, takes its time. I found his comics documentation of the passing scene, and his personal essays, to be particularly affecting.

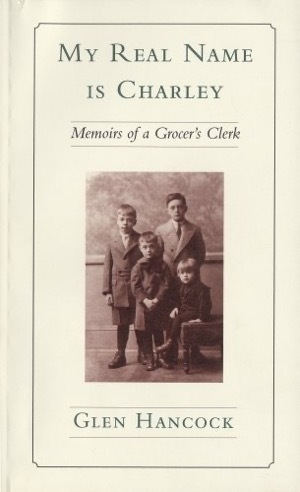

My Real Name is Charley: Memoirs of a Grocer’s Clerk by Glen Hancock

Hancock’s book is a gentle, readable memoir of growing up in Wolfville, NS, and of his life and the town’s life in the years between the world wars. He remembers the town as an enchanting place:

Wolfville is both commonplace and exclusive. It was, in common with other small Canadian municipalities, a heritage of empire, of small beginnings, of ups and downs. But as it is with people, towns have a personality of their own, a heritage that dwells in the heart, and in that way each is different.

The book follows the ups and downs also of his family, with parents who separated (he never discovers why) yet never divorced, the failure of his father’s fortunes during the Depression, and the eventual build-up to WWII. I loved reading his reminiscences of the life of Wolfville when that area of Nova Scotia was a vacation spot with twice-a-day trains, the smallest registered harbor in the world, and yet – like most of NS that time – still a largely rural, farming lifestyle.

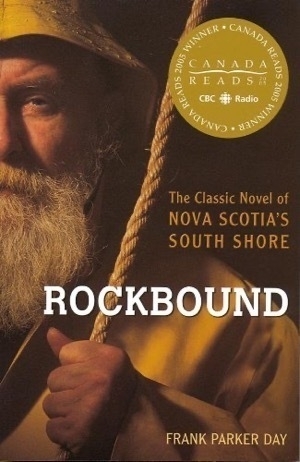

Rockbound by Frank Parker Day

I’ve used the word “gentle” for the first two books of this post, but that adjective definitely does not apply to Day’s novel, first published in 1928 and not reissued till 1973.

Blurbed as “The Classic Novel of NOVA SCOTIA’S SOUTH SHORE”, the novel follows the struggles of young, orphaned David Jung as he returns to the island of Rockbound to build a life for himself. To do that, though, he needs to work for his great-uncle, the tyrannical “king of Rockbound” Uriah Jung. The novel’s picture of the hard, primitive life of a small fishing community in the early 1900s is rich in detail; I could feel the cold, the greed, the back-breaking, skin-cracking toil needed to scratch out a bare existence from both the island and the sea.

The at times melodramatic story provides spaces where Day folds in absorbing scenes, such as a Saturday night fish-cleaning, a hurricane at sea that destroys large fishing schooners, and the protagonists’ race to get a dark lighthouse up and running to prevent disaster. It also has a day-to-day texture that, while no doubt heightened, feels plausible. According to the book’s afterward by scholar Gwendolyn Davies, Day was vilified by the inhabitants of an island called Ironbound who said he had befriended them only to gather scurrilous details for his novel that painted an untrue picture of their communities.

Rockbound’s canvas is large enough to take on one character’s possible madness and a deal with the Devil that breaks open the story to take it places it could not go by staying solely with the more naive and sensible David. The novel loses its balance occasionally; while I appreciate the maritime detail about fisherman gear and boats, I honestly understood very little of it. And in the book’s latter third, David’s friend Gershom Born pretty much takes over the narrative. The book’s voice is somewhat antique today, and others may be put off by the island dialect, though I found that to not be a problem.

In the reviews I read of the novel, no one mentioned a foreshadowing technique Day deploys a few times in the book that got my attention.

But it’s not quite foreshadowing. Three or four times in the book, Day focuses a paragraph or two on a specific minor character, and then jumps ahead a year or 30 years to show that character’s fate. Then the story steps back into the flow of the main narrative and this short interlude is never referred to again. It’s an odd device that poked my imagination somehow and extended the story in a direction that Day could not have done otherwise. (Come to think of it, the movie Y Tu Mama Tambien uses that device also.)

For example: the female characters are generally two-dimensional (as are many of the men in the large cast of characters) and Day rarely gets inside their heads. But there’s a passage in Chapter 3 that really shifted me.

The scene is the Saturday-night fish cleaning, where the day’s catchings are gutted, cleaned, and salted in preparation to sell on the mainland. It’s hard, painful, mechanical work, and all hands are expected to be in the barn to help out. Here’s where Day spends some time on Fanny:

Fanny was certainly a fine creature, but her morals were those of the birds. She came from Big Outpost to hoe Uriah's cabbages and potatoes, since the men had no time to work about gardens. Moreover, gardening was distinctly woman's work. All day long she hoed and weeded and gave a hand at night in the fish house, as did all the island women when a run of fish came. She trudged home from the fields in the late afternoon, hoe over her shoulder, whistling blithely. Before supper she always went to the beach, stripped and washed herself--little cared she if the men peeked--and put on a clean shirt and a fresh dress of blue and white in tiny checks. Her dresses, scrupulously washed and ironed, were kept in her father's sea chest in the loft by her bed. In the midst of all the dirt, stench, and disorder, she had an instinct, well-nigh a passion, for tidiness. In another setting she might have borne herself with the greatest lady in the land. She was great-hearted and could never refuse a strong fisherman half-crazed with lonely passion. When the women talked to her and said: "A little of dat's all right maybe when you'se young, but if you keeps on you'se'll never git a man," she used to reply, "We was made for de good of mens, an' mens is going to have me." If Uriah and his wife, she thought, cared so much for morals, why had they put her and Leah Levy to sleep in the loft with the sharesmen?Sure enough, she never got a man, but she bore three daughters that grew into stout lasses, knowing no more than Fanny who were their fathers. In after years Gershom used to say, “I t’ink de pretty one wid de yaller hair mus’ be mine, but de dark ugly one favours Noble Morash.” Fanny saved her pennies and looked after herself, and when she was too old to work bought a little white cottage in Liscomb. When she was very old and felt herself at the point of death, she sent for her three daughters, but they refused to come. They had all married and were ashamed of their mother. One morning the neighbours found her dead on her clean-valanced couch, even in death smiling bravely upon a world that had taken her all and paid nothing in return.

But that is going far ahead of this story, for the Fanny who bickered with Gershom Born that night in the fish house was only a wild, gay girl of eighteen. She wore, like the others, oilskins spattered with herring blood, and a sou’wester to protect her yellow hair.

The juxtaposition of those images – of Fanny dying alone, abandoned by her daughters, against the fresh and energetic spitfire of 18 with her two little girls in tow – and that heartbreaking “a world that had taken her all and paid nothing in return” – really got to me. In some ways it got to me more than David’s story did. Whenever Fanny appeared afterward in the book, I could not shake that picture of her dying alone on her couch.