Finished reading: A Year’s Turning by Michael Viney 📚

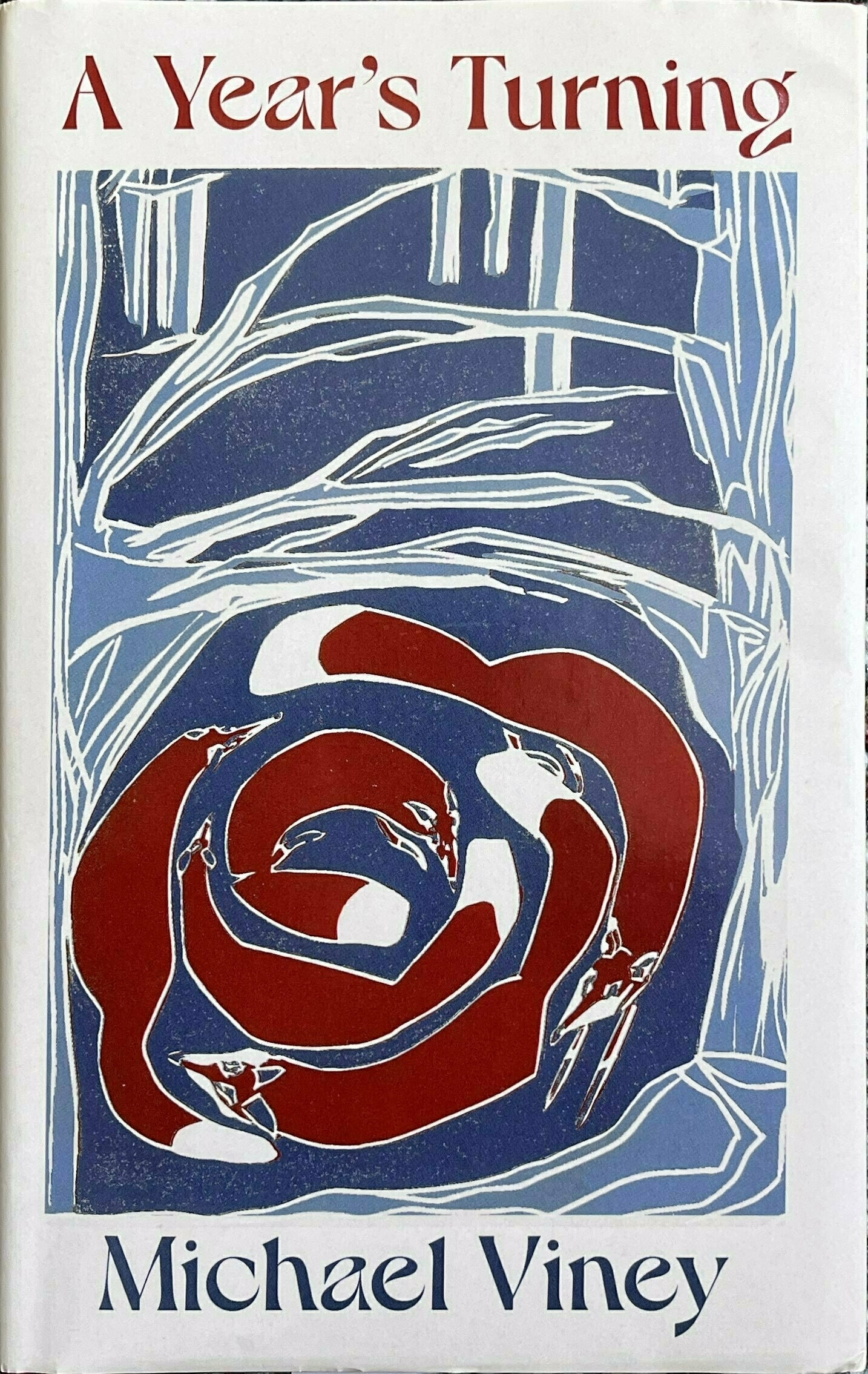

Purchased in a bookshop in Galway because I had not yet purchased any books while in Ireland and I felt I really needed to. And lord, that gorgeous cover illustration by Sheelyn Browne. Viney’s book of natural history, fact, lore, memoir, prose poetry, and his own drawings originated from columns he wrote in the mid-70s when he, his wife and daughter moved “back to the land” in a rural area of County Mayo on the West Coast of Ireland. The book was originally published in 1996 and reissued in 2022.

The essays – one for each month of the year – serve as a naturalist’s notebook of poetry, observations, history, science, and life in a remote and empty area of country. I had quite a bit of trouble following the thread of his essays until it occurred to me to mentally insert a few lines of white space between topics here and there; seeing these passages as entries in a scrapbook (with no need for transitions) made the chapters as a whole make more sense.

The book is studded with wonderful bits of lore and fact: phenology is the study of nature’s calendar; “botanists have calculated that spring moves north across flat ground at roughly two miles an hour” while trees begin to redden from north to south at about 40 miles an hour; primroses bloom early (prima rose, the first rose) to capture light and moisture before woodland trees start to leaf. “Woodland suits primroses because moisture evaporates more slowly in the shade.”

Viney’s prose can be intensely poetic and evocative:

There are at least seventy sorts of blackberry along the hedges of Ireland now, some hauling themselves about with briars the thickness of my thumb and armed with hooked prickles of a medieval ferocity.

But the writer’s attempt to put his love into words sometimes makes the prose giddy on its own perfume:

How lush, by comparison, our ‘bleak’ Mayo hillside, how sprawling and coarsely tangled and seething with flies and bees! But down on the duach, at the margin of the lake, there was an echo of the spare and precious flora of seventy-seven degrees north. For eleven months of the year, the closebitten sward is a sodden green carpet mostly innocent of blossom. And then, in August, its wettest parts put up a flush of chaste and beautiful white flowers.

What impressed me was, even in the mid-90s, Viney’s chronicling of environmental change. The hillsides that had been unchanged since the years of the Famine were seeing more plastic as litter in the landscape and in the ocean, more roads, the disappearance of species, the fading away of older generations who knew and appreciated the old ways of living in harmony with a sometimes harsh but often beautiful nature.

Think of what it means to doubt the ’naturalness’ of weather. We have never been sure what it would do, but we could be fairly sure of what it would not do, on average and over a period. Given a windy winter like this one, we could count on ‘fickle’ nature not to do it too often or too catastrophically. But supposing we lost that assurance: supposing, after sixteen storms since Christmas, we had good reason for trusting that there would not be sixty more? …

It cannot help that the people who might make decisions about global warming are themselves so totally insulated from natural things and especially from weather. One sees them on television, being ushered beneath umbrellas from one heated capsule to the next. What can they possibly know of life amid wind and rain?

Also: a 2022 article from the Irish Times on Viney’s 45-year history with the newspaper.