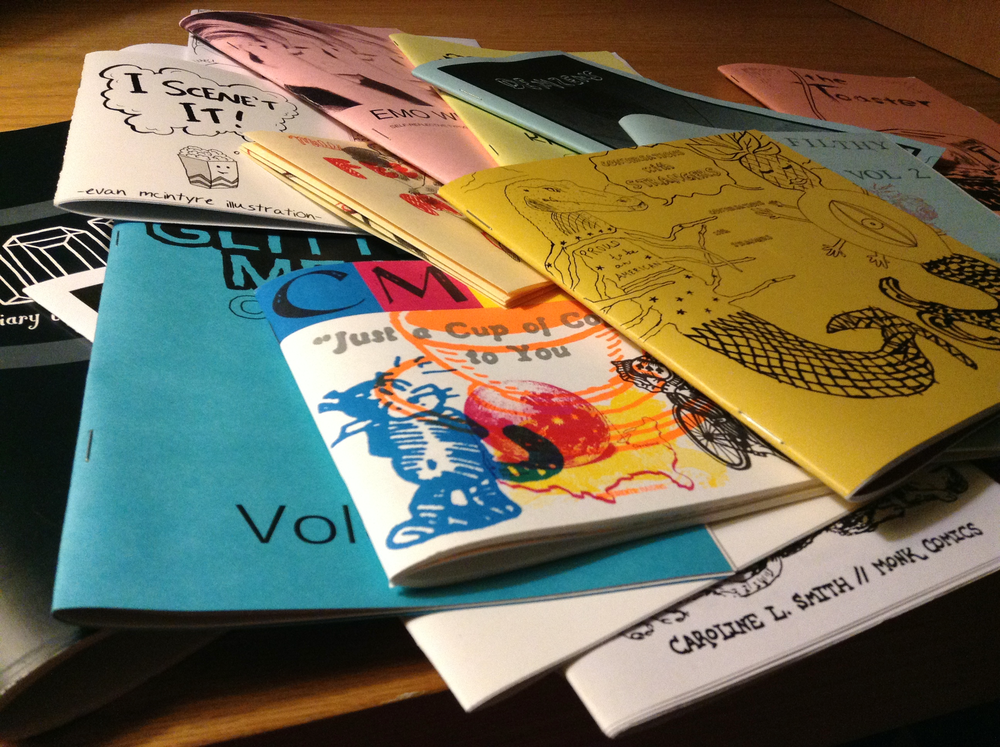

My haul from the April '16 Zine Machine Printed Matter Festival

[caption id="" align=“alignnone” width=“2500.0”] My zine haul[/caption]

My zine haul[/caption]

My first exposure to zines was courtesy of The Paper Plant, a downtown Raleigh new & used bookstore and literary press in the late '80s that featured weekly open mic nights and lots of local and national zines. I was fascinated by the homemade, raw energy of these little paper pamphlets.

It was probably from there that I found Mike Gunderloy's sublime Factsheet Five. Before the Interwebz, kids, there were homemade zines printed on the office copying machine on the QT and a postal network that linked their makers. Factsheet Five was a paper-based record of the zine scene, with every issue containing literally hundreds of mini-reviews of all types of publications.

Send Mike Gunderloy $20 and a SASE and he would send back a random assortment of zines: humor, comics, opinion, music, collage, art, poetry, diary, politics -- the choice was overwhelming. As someone who had spent four years in a relatively isolated region of the Old South, I could not get enough of the color, energy, verve, and connection that the zine culture promised.

That promise was all around me in April 2016 at the second annual Zine Machine Festival. The Durham Armory hosted long tables of mainly artists selling their self-made paper goods -- posters, art, comics, zines, stationery -- and other art objects too, like jewelry, fabrics, and so on.

It was such a great scene -- so much color, so much liveliness, so much love for paper ephemera. And so different from the comic-book conventions I used to go to. Compared to those types of events, the Zine Machine was smaller, not flashy or gaudy, quiet enough for you to talk with the creators selling their creations, more homey and friendly.

The Zine Machine folks are citizen artists, if you will -- out there making art, studying, holding down day jobs, supportive of their fellow artists and makers (or so it seemed to me) and traveling to sell their zines on the weekends.

I was struck by how young so many of them were; I was definitely one of the oldsters wandering around. The Triangle Printed Matter Facebook group was represented by several of their publications, and they looked to be all glowing and energetic twenty-somethings.

It was so great and heartening to see young people making art and being part of a community. No one is getting rich off of this, and maybe not even covering their expenses. But going to zine and small-press conventions and gatherings is a rite of passage, and if you're a zinester, you gots to do it.

I took, I think, $50 in cash with me. When I spent it all, that was the signal it was time to leave.

I paused often, though, to just look around and soak up the atmosphere. I thought the same thought as when I pored over Factsheet Five 30+ years ago -- God, it'd be fun to do that.

Herewith, some quick takes on the stuff I got, with links to the artists' sites.

Caroline L. Smith: Monk (daily diary comics), it's all about CATS, A Picture of the Universe. Caroline produces diary comics, with "Monk" a record of most of 2015; "CATS" is a subset of the diary comics where her cats take center stage. I like reading diary comics and this is a solid collection. "Universe" is an ambitious blend of tech-writing and comics, rather like Larry Gonick's "Cartoon History of..." series, showing off what Caroline can do with more formal storytelling and design.

Filthy, Vol. 2: Self-Portraits from filthyzines at gmail dot com. Assemblage of stiffly hand-drawn stuff, photos, collage, hand-lettered pages, typed pages -- a real mish-mash that reminded me of the zines of old. It's so personal I can't make head or tail of it and I don't care. The need to communicate and get whatever was inside onto the page, is here.

Glittermeat Comix (Tumblr) (Etsy): Glittermeat Comics, Glittermeat Comics: Volume 2, Famous Meats in History. These standalone gag strips are the unacknowledged love child of The Oatmeal and Perry Bible Fellowship. The artist has a confident visual style and snarky attitude. I'd buy more of these sick and disturbing little puppies.

Evan McIntyre:I Scene't It! A colorful mini with each page devoted to a still-life, scene, or colorful detail, real or fantastical. My favorites: the ambulance in flames and the back of a guy's bald head and neck, covered with a huge band-aid.

Adam Meuse: White Cards, Drawing Is Hard. "White Cards" is Adam's collection of filthy, sexual (not sexy), and scatological drawings he sketched on little white cards used at his soul-killing job. The scenes often include his co-workers (a photo of them is on the endpaper) so they must have 1) gotten a kick out of them and 2) shared his rough humor. Physically and emotionally brutal and tedious jobs can do that to you. That said, the man is a damn good cartoonist and I'd kill to be able to sketch that well. "Drawing is Hard" is a more formal and professionally polished product as the artist protagonist discusses his and his work's worth with his walking talking brain and his walking talking heart. A nice little fable and pick-me-up for the creative zinester.

Desi Varsel: Emo Web Art: Self-Reflective Typography, #ABOUT The Artist. Loved the sweet little "ABOUT The Artist" mini. "Self-Reflective Typography" is a large-format mini, a short personal/journal zine of painful experience.

Barefoot Press: CMYK. This was a free mini showing off their pretty incredible color separations, design, and print quality. Stands on its own as a hand-held art gallery.

James McPherson: Let's Be Honest With Each Other For A Moment (A Total Let Down of a Story). Clown Kisses Press was represented by James and Rellie (see next item). "Let's Be Honest" is a mini that also looks like a formal experiment with pattern, design, and typography, telling an elliptical kind of first-person anecdote. I read, I frowned, I nodded, I moved on.

Rellie Brewer: Feeling Myself And You. An accordion zine. Loved the fluidity of her figure drawings and the hand-lettering of this paneled poem. I also bought her print "Dance Thru", a large color print of two entwined figures from the zine. A young woman at the Triangle Printed Matter table gushed when she saw me carrying it and I pointed her to where I'd got it. I love spreading the love.

Triangle Printed Matter Club: Conversations With Strangers. Anthology zine, with contributions from club members on the title theme. Comics, poetry, collage, and -- the most interesting things I read in any of the zines -- Jeff Stern's transcription (in teeny tiny type) of "The conversation among strangers ... recorded by hand 10/15/93 in an Amtrack 'club car' (the part of the train where smoking and drinking were allowed) in transit from New London, CT to Amherst, MA approx. 11pm-3am." Wired, loopy, rambling, hard to follow, and I couldn't stop reading it.

Eric Knisley: The Toaster, Denizens, Memory Murder Mystery, Fight Scene. Eric is a long-time denizen of the local comics scene and the stuff he draws and shows at the local Durham Comics Project meetups are jaw-droppingly good; I love the confident line and fluid anatomy, and the sometimes crazy level of detail in his bigger pieces. I bought four of Eric's zines that he's created over the years for 24-Hour Comics Day.

"Memory Murder Mystery" is stream-of-consciousness interior-noir while "The Toaster" is a dark parable of some kind, though I try to resist reading too many layers into a comic written and drawn over 24 hours.

"Fight Scene" is a fun and funny superhero/supervillain smackdown, where the banter between the foes takes an unexpected turn. My favorite is "Denizens," 24 full-page pictures of 24 unusual characters with a paragraph of character description for each. I enjoyed discovering the story that began to emerge and weave itself from those descriptions to tie these disparate characters together.

I got Eric to sign all 4, so I think I did all right.