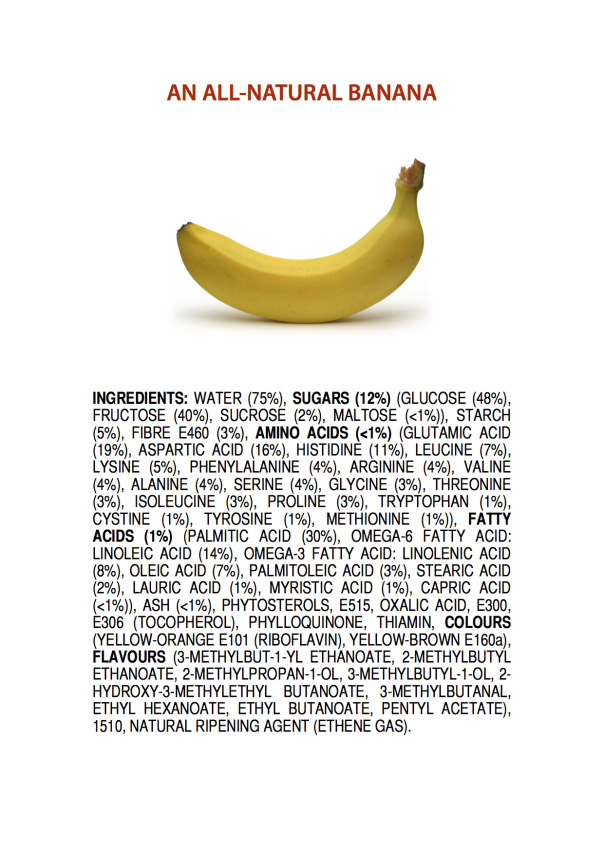

One of the chief rules of tech writing -- or at least one of my chief rules -- is to not dump into the manual every scrap of information I have on hand.

One of the chief rules of tech writing -- or at least one of my chief rules -- is to not dump into the manual every scrap of information I have on hand.

The tech writer's job is to present, to select, to shape. As with art, it's not just about what you put in, it's about what you leave out.

One of my freelance jobs was to create a help file for a program on crop genetics, a knowledge domain that was literally beyond my ken. I could not hope to understand the ins and outs of how to use that program in the six short weeks I worked on the project because I couldn't understand what it output and what you could use the output for.

In that case, I opted for my standard fallback plan: make the help file procedural (describe the mechanics of using the program) rather than conceptual (the big ideas and concepts on crop genetics that inform the program's design). If you don't know where to start, go with procedural first: most users are simply bewildered by a new application's user interface and appreciate any sort of road map that helps orient them to basic operations.

Then, after you've played with the application for a while, you can begin to divine a little more of its purpose, what it could be used for, and perhaps how to write topics that make more specialized operations easier for the user.

I'm not a scientist, but I am an avid user of applications. I can play with an app, push buttons, look at file extensions, note the preferences options, and pretty much plot the entire outline of a procedural help file in my head. I was lucky enough to have the developer and some expert users at hand, so I could quiz them on common workflows or on what a beginner would need to know vs. an expert user. Through playing around, reading old documentation, and interviewing experienced users, I created a help file/user guide that I think got most users 80 percent of the way there. For a product that had no help file before I got there, I think it was a good start.

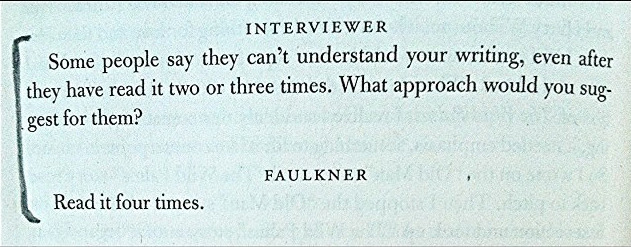

What would have sunk the project was to pretend to know more than I did. Had I simply dumped my notes onto the screen, in the hopes of conveying the false impression that I knew what I was writing about, then I would have done the user a disservice. If an application's interface is inscrutable and upside-down, then a help file that is equally obtuse or eccentric is simply another insult thrown in the user's face. It means I have not served as their stand-in and advocate. Instead of me making sense of the application so that they could use it to meet their needs, I have instead forced them to do the sense-making.

The old saying goes "if everything is important, then nothing is important." It's up to me to select what's important for the user to know, what is less important, what is not important. I put those choices into the document, release the document into the world, and wait for the feedback that tells me whether I got it mostly right. If I'm lucky, I get another chance to make the next version a little better.

It has been only very recently that I've thought about how this lesson applies to life. Or my life, in particular.

The way I've typically spent my time and filled my head is to stuff myself full of projects, both urgent and non-urgent, real and imagined: acting, arts classes, writing groups, neighborhood board, yoga class, reading, writing, brainstorming a new side business idea, watching every episode of "Parks and Recreation" or "Clatterford," moving every icon on my MacBook desktop 10 pixels to the left, opening every PDF downloaded in 2013 to judge it worth keeping -- in short, an insane amount of activity.

As I've pared away my responsibilities outside the home, and in general slowed down my analytical thinking, I've noticed how I've splattered my energy and attention all over the place. I enjoyed myself, no doubt about it, but I was always a little frantic too.

Because, I think, I had not done my job and selected what was important, what was less important, what was not important. I did not choose. Choosing was actually quite terrifying because I have always had a case of FOMO ("Fear Of Missing Out") (Wikipedia, Article). The series of posts I did on being an information packrat echo this theme: the present-day discomfort of hoarding anything -- information, experiences, books, salt-and-pepper shakers -- is easier to bear emotionally than any supposed pain of missing out on something in the future. The chaos in my head of trying to DO IT ALL, of making sense of all this stuff, of attempting to manage it, was stressing me out.

Recently, on re-reading and re-listening to the works of Michael Neill, George Pransky, and Sydney Banks, I decided to reduce my multiple input streams and multitasking and multiple-priorities. As best I could, I chose to sit quietly a little more often than I do. And have a little less on my mind. My mind is forever a-buzzing with ideas and projects and strategies, and I was exhausted. It was time to choose and edit which thoughts to listen to, which ones to let go, and which ones could wait for a while.

Letting my thinking settle down has, to a degree, also slowed down my manic need to fill my day with activity. I don't know why that is, but it is. I'm not initiating many projects or meetings nowadays. I'm not furiously brainstorming my next side-business idea and trying to figure it all out. I'm re-reading a book instead of rushing to the next one. I try not to chase the next thing I simply must do before doing the next thing. Everyone has preferences and I'm able to hear them a little better now that the noise in my head has subsided.

As for distinguishing between mindful activity and mindless web surfing, well, I'm still working on that. It's like distinguishing between craving and hunger; I know what will make me feel more satisfied later so I know what choice makes sense now. Sometimes I do binge, and that's OK.

Another saying in the self-help world: "how you do anything is how you do everything." I hope I can learn how to do in my life what I'm able to do pretty successfully in my work. It takes time and practice. There are false starts and do-overs. I'm on the lookout for feedback that tells me whether I'm getting it mostly right. I hope to make the next version a little better.