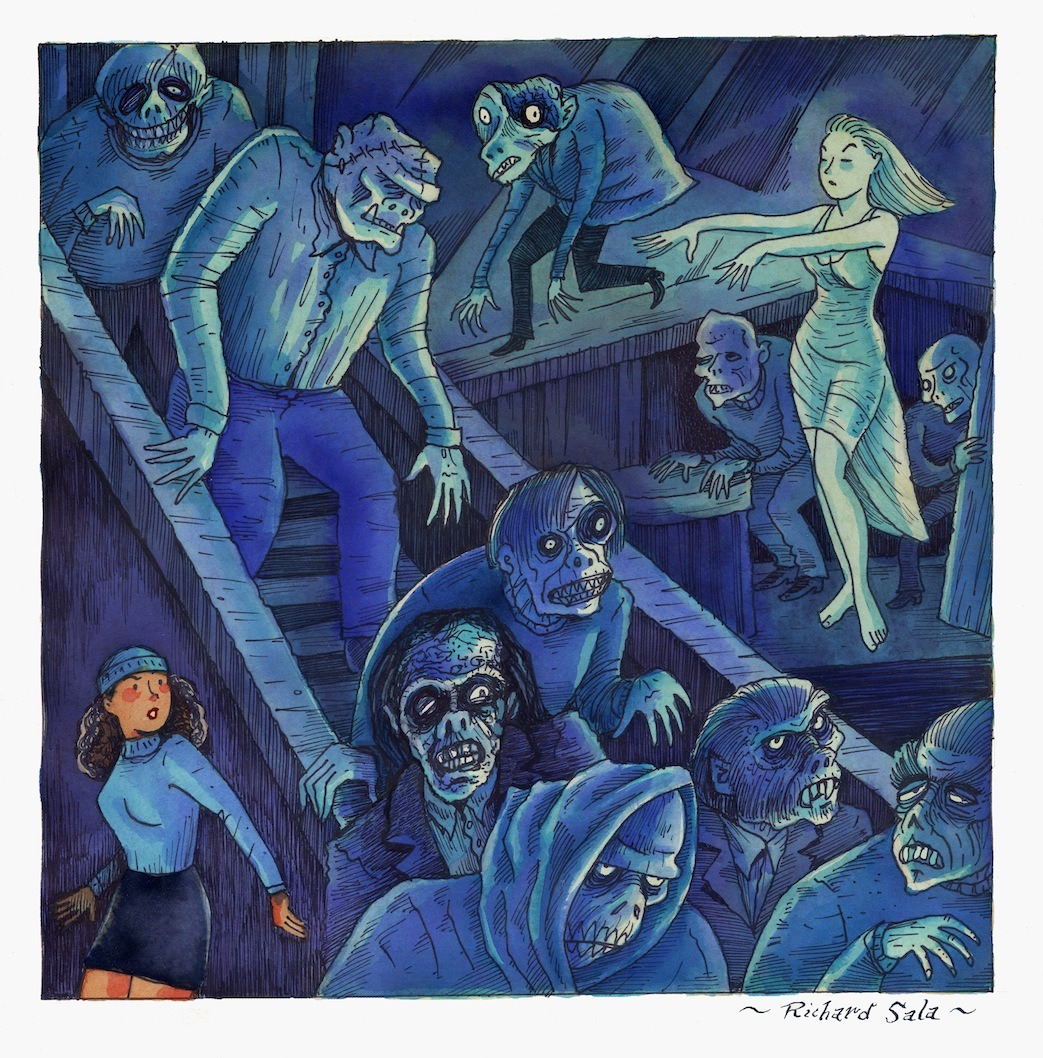

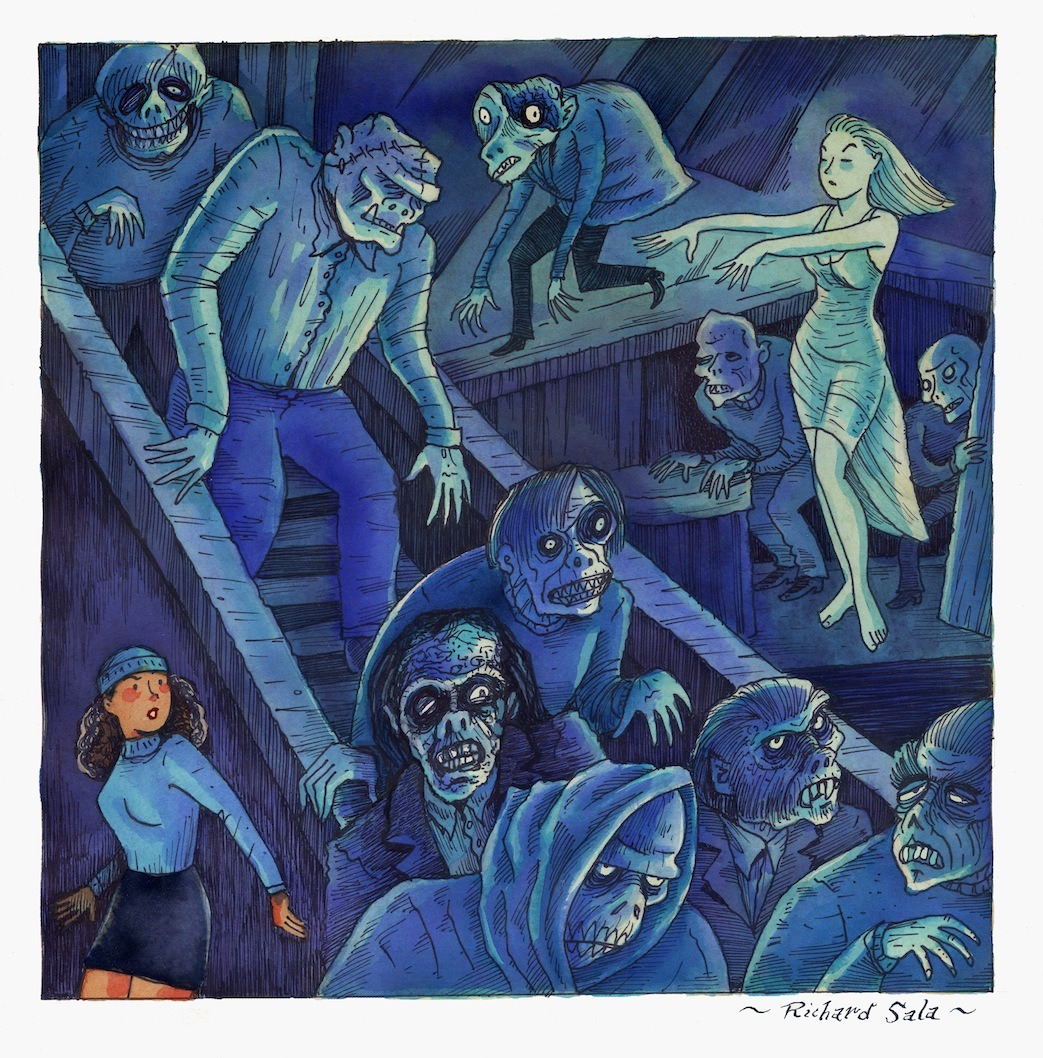

Richard Sala: Colleen's Dream

“Colleen’s Dream” (An outtake from my book THE HIDDEN). To read the story behind it, see Here Lies RICHARD SALA: An Outtake from The Hidden ~ Colleen’s Dream

“Colleen’s Dream” (An outtake from my book THE HIDDEN). To read the story behind it, see Here Lies RICHARD SALA: An Outtake from The Hidden ~ Colleen’s Dream

This is one of the rules that has served me well, as a Program Manager at Microsoft: Carve out time for what’s important.

You don’t have time, you make time. If you don’t make time for what’s important, it doesn’t happen. This is where The Rule of Three helps. Are you spending the right amount of time today on those three results you want to accomplish? The default pattern is to try and fit them in with all your existing routines. A more powerful approach is to make time for your three results today and optimize around that. This might mean disrupting other habits and routines you have, but this is a good thing. The more you get in the habit of making time for what’s important, the more you’ll get great results. If you’re not getting the results you want, you can start asking better questions. For example, are you investing enough time? Are you investing the right energy? Are you using the right approach? Or, maybe a different thing happens. Maybe you start accomplishing your results but don’t like what you get. You can step back and ask whether you’re choosing the right outcomes for The Rule of Three.

Here are some things to think about when you’re carving out your time:

This is a tip from my book, Getting Results the Agile Way (now on a Kindle), a time management system for achievers. You can test drive the system by taking the 30 Day Boot Camp for Getting Results, a free time management training course.

Give a person a fish and you feed them for a day. Teach a person to use the Internet and they won’t bother you for weeks, months, maybe years.

Today’s dose of wisdom « Getting Things Done in Academia

(See also: Teach a man to light a match, he warms himself for a day. Set him on fire, and he’s warm for the rest of his life.)

Trollope said, “On the last day of each month recorded, every person in a work of fiction should be a month older than on the first.” We go with our characters wherever they lead us, and as time makes its mark on us, so it must on them.

HALLIE BURNETT

If you acknowledge all this resistance and act on your plan anyway, you will make one of the most liberating discoveries possible for a human being—that you can take constructive action in any moment no matter what you feel, and no matter what excuses occur to you.

In short, you are free. Thoughts come and go. Feelings arise and fade. But none of them need to stop you from living a meaningful life based on your values.

Sometimes we do find the words to express an idea, and only then realize what a stupid idea it is. This experience would suggest that our thoughts are not as clean and beautiful as we would like to believe. Instead of blaming language for failing to capture our thoughts, maybe we should thank it for giving some shape to the muddle in our heads.

Working from home means you can work any 18 hours of the day that you choose.

The MikeBook has been receiving tons of app upgrades due to Lion (haven't upgraded yet; waiting a few months for the bugs to shake out).

In general, the app upgrades have caused no problem except for Safari, which disabled the Page Up, Page Down, Home and End keys. I mean...what?? Sorry, Apple, but I don't have a Magic Trackpad, and I still use my quaint little keyboard to navigate through my web pages.

Fortunately, a poster to this thread on the Apple support forum provided the secret handshake:

So, using the wonderfulness that is Keyboard Maestro, I remapped my Home, End, Page Up, and Page Down keys to the above keystrokes. Now, I can use my keyboard the way God (and not Apple) intended.

In 2007, John Maloof ran across a storage locker at a thrift auction house that contained over 100,000 negatives of pictures. The photos spanned the years from the 1950s–1990s and were primarily urban scenes of Chicago and New York. Maloof began posting the pictures on a blog and dug into the life of the woman who had taken these pictures: Vivian Maier. It took a lot of detective work, but it turned into a labor of love for Maloof, who has parlayed his interest in Maier and her photos into a handsome site, exhibitions, a film, and a book.

I particularly love her urban photos, seemingly taken on the fly, the sort of thing you might see yourself as you briskly walk past a street person or sightseers or a woman talking on a telephone. They’re wonderfully evocative of a different place and time.

Hoffman explains the nature of his work by offering an extended analogy. In the process, he deftly summarizes a lot of Eastern spiritual teachings.

Unfortunately, the clip omits Hoffman’s concluding line—one that throws the premise of many self-help books into question. Here’s that line:

“When you get the blanket thing, you can relax, because everything you could ever want or be, you already have and are.”

That statement might be a profound paradox—or pure nonsense. What do you think?

Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face. — Mike Tyson

Ran across this delightful post from a used bookseller in Pennsylvania. He acquired the July 1922 edition of Flapper magazine and reproduced an uncredited article that listed phrases and jargon that, while probably quite cheeky at the time, seem quaint and amusing now. It's fun working out the chain of associations that lead from the slang to the definition.

I wonder really how old the writer of the article was; I smell a fuddy-duddy who wants to appeal to the "with-it" generation. I could imagine a Beatnik or Hippie dictionary article of the same stripe.

Some of my favorites:

L.A. King and C.M. Burton in an article entitled, The Hazards of Goal Pursuit, for the American Psychological Association, argue that goals should be used only in the narrowest of circumstances: “The optimally striving individual ought to endeavor to achieve and approach goals that only slightly implicate the self; that are only moderately important, fairly easy, and moderately abstract; that do not conflict with each other, and that concern the accomplishment of something other than financial gain.”

If you can write - and you also write a superb script (not the same thing) - producers will want to meet you and stuff will happen. It’s all about the script. Don’t sell it short. Don’t let it go off half-cock. Plan it. Mull it. Research it. Filter it. Replan it. Write it. Rewrite it. Edit it. Put it to one side. Forget it. Then get it out. Read it. Re-read it. Edit it. Then put in some more jokes. Then cut some of them out. And check it over again. It might then be ready to send.

It takes ages. Even if you’re talented. Perhaps the proliferation of competitions gives people the idea that anyone can have a go because writing is easy. It is true that anyone can have a go. But it isn’t easy. I’ve been doing it for over ten years professionally and only now am I starting to think I might have the beginnings of a clue as to what I’m doing. But I do know this. Talent is fine. But there is no substitute for hard work.

I have lately been enjoying a blog by Austin, TX artist/writer Austin Kleon, and have been happily plundering his archives for posts on sketching, storytelling, art, and the like.

I was charmed by this post: Writing The Fibonacci Sonnet. It's a neat little writing trick that uses the Fibonacci numbers (1,1,2,3,5,8, 13, 21) to create short short stories with sentences that have one word, one word, two words, three words, and so on. Kind of like haiku, except counting the words in the sentences instead of the syllables.

It also reminds me of the poet Jonathan Williams' dotty "meta-four" poems, where each line only had four words. An example of one of his meta-four poems in this Guardian UK obit. Here's a meta-four from another appreciation of Williams:

estimated acres of forest

henry david thoreau burned

down in 1844 trying

to cook fish he'd

caught for dinner 300

My favorite instructional books acknowledge our psychic complexity. Rather than offering a smorgasbord of “techniques” and “tips,” they offer a process for making a modest change in our behavior and observing the results in an objective way. The moral of this story for writers: Don’t preach to me from on high. And don’t assume that what works for you will work for me.

Compulsively, we compare ourselves with those around us and find our lives wanting: other people seem to have found meaning, while we’re still searching. Partly, that’s because we have no direct access to their inner torment. But it also may be because they’re not looking for meaning in the first place. Perhaps that’s a blessing of sorts, but it’s hardly the enviable state of fulfilment we imagine must suffuse their lives. Being the kind of person who seeks answers in life is troublesome enough. There’s no point feeling inferior to those who aren’t even asking the questions.

via s3.amazonaws.com

One of the things I discovered about myself during the past year is that I'm a student, not a scholar. I've always thought of myself as a "lifelong student," but I'm not sure I really understood what that meant till recently.

In my view, a master's candidate is a student, a PhD candidate is a scholar. The differences are many: the difference between being an amateur (student) and a professional (scholar), between minor league and major league, between levels of commitment in terms of time, energy, passion, and dedication.

For me, a lifelong student retains the joy of learning new things and loves sampling the buffet. That's been me, that will always, probably, be me. The scholar, I think, takes a deeper interest and is best served (at least in their early years) by not flitting from flower to flower. Also, the way academe is structured, scholars are professionally groomed for a tough job market; the decisions they make today on the research they publish will have repercussions years down the line. The student, I think, lives more in the moment, or at least has a shorter time horizon for the satisfying of their desires.

As I'm sure I've said in other posts, I like taking classes. This seemed to separate the student from the scholar, in my brief experience. I think I'm one of the "Scanners' that Barbara Sher describes in her book Refuse to Choose: someone who loves the novelty and variety of learning and resists constraining themselves to a single specialty.

Reminds me of these quotes by Bill Moyers on the fun of being a journalist:

A journalist is a professional beachcomber on the shores of other people's wisdom ... A journalist is basically a chronicler, not an interpreter of events. Where else in society do you have the license to eavesdrop on so many different conversations as you have in journalism? Where else can you delve into the life of our times? I consider myself a fortunate man to have a forum for my curiosity.

Had I stuck it out in the PhD realm, my chosen research style would have been that of a journalist. The challenge for my life now, I think, is to elevate that curiosity and focus from a hobby done in my spare time to a respected place of prominence at the center of my life and how I choose to spend the rest of my years on the planet.

Of my master's degree progress, that is.

I took my comprehensive exam on Friday. At SILS, that is writing 6-8 pages on one of two essay questions that are emailed to you at the start of the day. You have until 3:30pm to finish the task. I started mine at about 10 am and wrapped up around 2:30pm, with a break for lunch. Essay questions are about the easiest task I could be given; I wound up writing 10 pages with I think good detail.

Today, Liz and I took a day trip over to Chapel Hill so I could return a stack of library books and pick up a copy of my advisor's comments on my master's paper. I thought I had done a good-enough job on the paper but that there were too many assumptions and maybe too much hand-waving and magical thinking in the Discussion and Conclusions section. I had spewed dots all over the page without seriously connecting them into a recognizable picture. But I thought the paper was at a stage where there was no more I really wanted to do with it. I could have spent days poring over the data some more, I could have done more research in the literature, and so on. That extra work would have represented the last 15-25% of effort on a paper whose value probably didn't warrant more time or energy. In any case, I'd held on to it long enough. It was time to throw it over the wall and see what my advisor had to say about it.

I was rather surprised at how minimal and non-eventful her comments were. I had rather mixed feelings looking over her comments, which were mainly to do with typos, awkward phrasings, mechanical errors, and the like. There were one or two "I don't accept your conclusion" remarks that I don't know how to address just yet; she gave no indication of what I should do to fix them. That's OK; it'll take less than 3 hours to take care of all her marked items and then format the paper per the school guidelines. Still - that's it?

I suppose what's interesting to me about the paper is how flimsy it feels to me. Had this been turned in by a doctoral student, I think it would have been held up to higher scrutiny and with calls for more justification of my statistics and assumptions. But I must remember: this is a master's paper, and the master's paper is probably the first and last research project most students will ever do. If they find they need to carry out a similar research project in their future jobs, then they have at least been introduced to the rudiments of the practice. That's the real goal of the paper. Contributing to the research dialogue is not a realistic expectation. (Though one of my professors said that many master's students look back on the paper as the most satisfying project of their academic career.)

In the end, I suppose, I believe that I did a good enough job, within my capacities and skills; better than others, perhaps, but not as good as I would like to think I could do. (And got closer to in my Chekhov paper last fall.)

Still, as with all things that have happened to me over the last few years in school, these are yet more opportunities for learning as I go.

As I see my schedule open up, with very few obligations on the horizon, I am starting to swell with projects that need to be started: selling off old textbooks, clearing my files of all the printed articles i read, cleaning out my closet, fixing stuff around the house, etc.

What stops me from slapping all sorts of projects into my planner book is another lesson I learned in 2010. I had stopped my banjo lessons due to the pressure of my other responsibilities. We still met weekly, to talk through what I was experiencing and trade strategies. Sometime after the semester ended, I think, I felt much relieved and wanted to resume the lessons. But he refused. His reasoning was sound: I may be in a quiet, stable phase at the moment, but we are not sure how long it will last. It would only put more pressure on me if I were to restart my practicing and then - BAM - life is firing more fastballs at me than i can handle.

And, as I recall, things happened as he said. Not long after, we had to start planning and executing the May workshop and life got crowded indeed. Even after the workshop was over, and life had truly settled down, he held off resuming our lessons. He was right. I needed the rest and needed to come back to a sort of equilibrium. Sometime after I left the program, we started up again and I've been chugging along with the banjer ever since.

All of which to say - I'm keeping my life underscheduled for the immediate future. My top priorities are revamping my resume, starting up a job search, figuring out what the next 5 years should be, etc. But no need to rush in. Relax the taut rubber band before it snaps and breaks. Relax, and pat myself on the head.

Libra Horoscope for week of February 24, 2011

An interviewer asked me, “What is the most difficult aspect of what you do?” Here’s what I said: “Not repeating myself is the hardest thing. And yet it’s also a lot of fun. There’s nothing more exciting for me than to keep being surprised by what I write. It’s deeply enjoyable to be able to feed people clues they haven’t heard from me before. And when I focus on doing what gives me pleasure, the horoscopes write themselves.” I hope this testimony helps you in your own life right now, Libra. If you’re afraid that you’re in danger of repeating yourself, start playing more. Look for what amuses you, for what scrambles your expectations in entertaining ways. Decide that you’re going to put the emphasis on provoking delight in yourself, not preserving your image.

I volunteered to do a tedious job at work -- copy/paste about maybe 200-400 parameters scattered throughout a group of FORTRAN files. The parameters may be in one of maybe 3 different formats. Also, the parameters came with multiline comments (with each commented line starting with !), and sometimes just big wodges of comments on their own that serve as documentation. The goal was to transform these snippets into something our customer could scan using Excel.

I volunteered to do it because it made no sense for a highly paid developer to do such a menial job; also, I kind of like taking on little challenges like this, developing a new technique or learn some new tools, and seeing how quickly I can rip through them. Then it's just a matter of putting on the headphones, pressing a few keys repetitively so the computer does most of the work, and voila.

I realized that my initial solution for this would be overly complicated, as it always is, and that the exploration process as I groped my way toward simpledom would be haphazard, as it always is. I thought "How can I use Applescript to parse the text? Should I just copy the fragments into Word and use Word's formatting functions? Should I use a text editor with some text formatting Services?" (DevonThink makes a killer set of text-formatting services available to Mac users for free; DevonThink not required to use them.)

I spent about 5 hours over the weekend scarfing up text-formatting Applescript code, messing with text editors, messing with Automator, messing with some copied fragments that I was using as my test case, messing with Applescript in Word (which adds its own complications), and seeing possible workflows getting more complicated.

Sometime around Monday evening my brain settled down and I decided on my workflow:

The intent of this workflow brings in what I've mentioned before, about batching similar actions together. With this workflow, I could check each line off as done and move fully to the next set of operations. I could do each set of operations more quickly and efficiently than transitioning from 1 to 2 to 3 to 4 within each file.

#2 gave me the headache, of course, and is where I spent the bulk of my think time. I had on blinders as I was sure I could use some sort of Applescript in Word that would reformat everything in one go, without needing multiple passes. And because I thought it could be done, I thought I had to do it that way.

However, I had set myself a time limit for the R&D, and I had passed it. Time to drop that all-in-one solution. As I looked at the line fragments, I noticed that the bulk of the work would be done in the first line of each multi-line fragment. OK, let's start there.

That shift brought me back to the Agile programming maxim of, "Do the simplest thing that could possibly work." This is when I turned back to Keyboard Maestro; it's not as powerful as QuicKeys (or my beloved Macro Express in the Windows world), but it's quick, dependable, and does the job. In this case, I was using it as a robot typing the keyboard, but that keeps it simple.

That's when I cobbled together my workflow for #2:

Hm. Well, that still looks pretty complicated, doesn't it? But it's faster than me burning hours to get my head deep into Applescript territory, with delimiters, variables, if-thens, and so on.

The other advantage of this workflow is that this should cover about 80% of the code I'll have to reformat. I now have a base set of actions that I can clone and customize to handle the exceptions.

Anyway, the lesson as always: don't overthink it. Keep it simple.