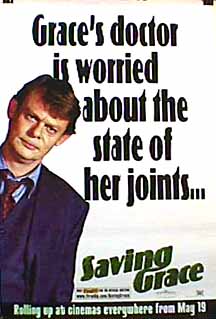

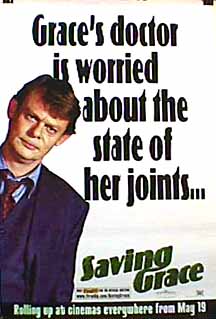

Telling the story of Doc Martin is a complicated business from the start: do we begin with the first movie, Saving Grace (2000), and then watch the two movies that followed-- Doc Martin (2001) and Legend of the Cloutie (2003)?

Or should we instead watch them as part of the character's chronology -- that is, start with the prequel Doc Martin and its sequel, Legend of the Cloutie, that lead in, kinda sorta, to Saving Grace?

In a way, it doesn't really matter since the movies have no narrative overlap with the TV series. Yes, there's a Doc Martin. Yes, there's a Cornish fishing village. Yes, there are a few key creative people behind the scenes who remain constant. But after that, the similarities stop dead. If you're coming to the movies after bingeing on the TV show, it's like glimpsing the face of a long-ago friend from a long way off, then realizing when you get closer they look nothing like you remembered.

But put the TV show to one side for now -- there's even a marked difference between Saving Grace and the two Doc Martin movies that followed. The Doc Martin idea that created an international television hit went through lots of changes from his first appearances onscreen.

Let's start with the best movie first, then. Saving Grace is a perfectly charming low-budget indie that the UK can do so well and the US can do hardly at all. Of course, the only reasons we're interested in it now, 15 years after it was made and released, are Craig Ferguson, Martin Clunes, and Doc Martin.

But before we get to them, let's talk about this as a movie, because it really is good fun. It has a good variety of light drama and farce, beautiful landscapes, wonderful actors, and a few actual themes that hold the movie together without weighing it down.

The cinematography, too, is lush. We see more of the surrounding landscape, more of the rugged coastline, than we do in the TV series. And for whatever reason -- the lighting, the lenses -- the pictures just look more ravishing.

And the main story, of a widow (played by Brenda Blethyn) desperate to raise money to save her home by helping her gardener (Ferguson) grow high-quality marijuana in her greenhouse, is strong comic material that gets the story moving (though it takes half an hour to get to this point).

Brenda Blethyn -- when she can tamp down the panic and nervous tics (always a problem with a Blethyn performance) -- is a sympathetic and resourceful Grace, who discovers what she's really made of as the pot deal begins going wrong and a French drug lord starts taking an interest in her potent homegrown product. There's a madcap, farcical finish and it all ends happily, as it should. The status quo has changed for all of the characters, even minor ones, and for the better.

Another factor in its favor is the script by Ferguson and Mark Crowdy (who will go on to have a long association with Doc Martin). Ferguson, at this point in his career, was a jobbing actor/writer/comedian/filmmaker and Saving Grace is one of a string of productions from those years. As an actor, he's funny, amiable, and has an easygoing presence. As a writer, he and Crowdy juggle a lot of characters, give most every actor at least a couple of scenes where they can show their stuff, and keep all the plot plates spinning at just the right speed to a satisfying payoff.

In the creators' commentary, the director Nigel Cole and Crowdy suggest that of all the cast members, Clunes was probably the one best known to a British audience due to his Men Behaving Badly sitcom. Clunes provides cheery support as Ferguson's pal, the pot-smoking Dr. Martin Bamford, and it's much of a piece with his other comic work up to that time. The Bamford character is a nice enough bloke, but bumbling and, by his own admission, not a very good doctor. Clunes turns in a fine but undistinguished supporting performance in the ensemble. It's not a star-making part.

No, the real star is Port Isaac, the Cornish fishing village cast as Port Liac in Saving Grace. When Ferguson's character, in a drowsy post-pot haze, stares out at the ocean and says, "I love it here," he's expressing one of the movie's strongest themes.

Because Port Liac is a place that draws people from all over to it. And more than that, it transforms them. It's the Land of Faerie where magic happens. The old joke of the village knowing everyone's business is true here, but it's not played for the same old laughs. The villagers know Grace's predicament and strive to let her keep her dignity, as much as they can. They even know about Matthew's pot-growing and simply turn a blind eye. The village truly seems to be a snug harbor for its residents and a welcoming wonderland for outsiders.

Which is why the next movie is such a nasty jolt.

Dr. Martin Bamford's arrival in the village in Doc Martin (set at some unspecified time before Saving Grace) is greeted with suspicion and gossip. There's a poison pen leaving incriminating photos under wobbly jelly molds (a wonderfully bizarre touch). Bamford is bullied and tossed about and harried by busybodies. There's even a town meeting to decide whether to expel him.

I mean...what?? Where the hell is the cozy quaint village from Saving Grace? Where did all of these mean, petty villagers come from? How in the world can bad ol' Port Isaac in Doc Martin evolve into to cuddly li'l Port Liac in Saving Grace?

What changed?

The first thing, obviously, was the creative team. Crowdy became an executive producer, Clunes' wife Phillipa Braithwaite became the producer, and Simon Mayle the writer. Crowdy, Clunes, and a few supporting actors were the only carryovers from Saving Grace.

The second thing that changed -- and not for the better -- was the creative reason for making the movie. I do not know the whole story behind why Saving Grace was made, but it must have struck Ferguson, Cole, et al., as a fun story to tell. One of the things that makes Saving Grace so much better than the movies that followed is that it is a finished work of art. Instead of the story continuing, there are no stories left to tell.

But Doc Martin was explicitly created to give Martin Clunes another TV vehicle and that prompts a different set of creative questions and decisions. Something about the character and the locale -- the Cornish fishing village of Port Isaac, where the movie was set -- struck a chord in the actor. It must have seemed both a landscape and a potential comic territory not being worked by anyone else.

Unlike some freelancers, Clunes took his career into his own hands by creating Buffalo Pictures, which co-produced the Doc Martin movies. By developing his own properties, Clunes could guarantee himself some ongoing employment and artistic and financial control over the production -- always depending, of course, if there was a buyer for the product.

Another consideration, surely, was to break free of his earlier Men Behaving Badly character. Clunes became the embodiment of laddish underachieving with the character of Gary Strang, which he played from 1992-99. It was a good run, but time to move on to other challenges. Although Clunes had made a few movies, mainly supporting parts, telly was his home field. (I can't find any indication that he's done stage work, though he surely has the voice for it.)

So instead of telling a story that needs to be told, Doc Martin needs to find a story to tell. And that puts different pressures on the writer. The brief was probably along the lines of, "Devise a way to get Dr. Martin Bamford to Port Isaac. Give him an adventure. He falls in love with the village. He stays."

Mayle, whose IMDB credits end with the two Doc Martin movies (isn't that interesting, he said, stroking his chin), had no end of constraints. As played by Clunes, Bamford is not markedly different from Clunes' typical juvenile male leads, so how can the writer make that kind of underdeveloped character interesting? (Bamford's love of the weed is not in evidence at all here or in Cloutie.) And Mayle had to create a storytelling vehicle that would fire off future TV stories featuring Bamford.

Very well then -- throw the character in a ditch, pile on the trouble, and see how he handles it. Trouble always evokes character, right? Start with an uncomfortably misogynistic plot point where he deduces his wife cheating on him with his three best friends, drag him through freezing wet moors in inky darkness, and then deliver the bedraggled, yet still remarkably mild-mannered, character unto Port Isaac, which is undergoing its own crisis. Get Bamford mixed up with the crisis right away, maybe even mistaken for the bad guy by the villagers. And simmer -- without ever coming to a full boil.

(Although, if you're making these movies as explicit prequels to Saving Grace, why change the village's name from Port Liac to Port Isaac? Ah, who cares -- it's just telly.)

Clunes is a fine actor and low-key comic performer, but in the TV movies his character is so mild, even when he's harried, that his presence barely moves the story's needle. Bamford never has a clear goal, seems to run away from rather than to something, and spends most of Act 2 searching for a cell phone signal. This is not promising.

Mayle responds to this by making most of the village characters hostile, suspicious, and generally unpleasant -- surely this conflict will rouse Bamford to life! But no, Bamford lifts his eyebrows at them in bewilderment or mild irritation before thumbing his cell phone to suss out a signal.

Piling on conflict can be a valid storytelling strategy, but the conflict should force the character to make dramatic decisions at some cost to himself. Which doesn't happen here. Even though the village eventually rallies round Bamford, there's no sense of triumph or accomplishment. Because the story was meant to end this way, there's little emotional satisfaction to Bamford's decision to stay.

Still, Mayle delivers a well-made script and he cleverly makes the bad guy the village doctor, so that when he's hauled away, Bamford is there to take his place.

With Doc Martin and The Legend of the Cloutie, Mayle has a different set of problems. Bamford is now the village doctor, an accepted member of the community, and looking for property of his own. He is no longer an outsider. What will generate the story conflict now?

Outsiders, principally, in the form of the obnoxiously scheming Bowden family, who outbid Bamford on his ramshackle dream home, and the two customs agents on the trail of suspected village smugglers.

It took me a long time to get around to seeing this movie, because the first 10 minutes of setting the stage, introducing the players, and hearing the plot gears wheeze into a sort-of shambling life just bored me to tears. I saw the movie in short bursts just to get through it.

And when Bamford goes into his elaborate plan to scare the newcomers by imitating the mythical "Beast of Bodmin", well, that was where I hung on out of journalistic duty and pouted through it. This is an idiot plot (as in, the characters have to behave like idiots for the story to work) and so I kept the movie at arm's length the whole time.

Cloutie is both well-made and middling; there are always more of these types of movies and plays than there are out-and-out bad or good movies. Its tone is a little more whimsical and less malicious, and the mysteries and potential dangers are teased out effectively. Bamford tries his absurd way to change reality, but falls back on the mystical, female-based, nature magic of the cloutie to do the trick. The Wiccan subplot is a fresh bit of storytelling that begins to open up the world of Port Isaac while grounding it in its rural locale.

Cloutie also tries to build an ensemble of actors and recurring characters. But this movie was broadcast two years after the previous Doc Martin movie -- would there really be that many fans who would remember the setup and recognize these characters, this world?

Ach, enough of this. Let's turn to the positive. People of color make an appearance in Cloutie, an event that doesn't even happen in the TV series (I haven't seen Series 6 and 7 yet). Also, there's barely a whiff of romance between Bamford and...anyone. He looks infatuated by Neve Mcintosh's character but does not flirt with her at all. With her long dark hair and direct gaze, Mcintosh sets the physical template for Caroline Catz's Louisa. But Cloutie reserves the love story for his Wiccan patient Lolita; Bamford, in fact, is instrumental in helping her meet the love of her life, which is sweet of him.

So the made-for-TV Doc Martin movies were not as good as Saving Grace and have not inspired confidence as a franchise. What do they get right? And do they have any assets the TV series could take advantage of?

The first thing the TV movies benefit from directly is Ben Bolt. His camera setups, framings, and movement (such as the point-of-view cameras for the poison pen and Beast of Bodmin shots) are a pleasant shock for anyone familiar with the consistent visual grammar he established for the TV series. He finds unusual, more visually jagged angles that make one see Port Isaac's buildings anew, and the movies find great big swathes of land where the camera can linger. The movies' situations, and more time to tell the stories, offer Bolt opportunities to experiment he will not get in the series.

I also like how the interiors are more cramped and shabby generally. This place looks more like a fishing village struggling through hard times -- you see how cold it is. This is not the chocolate-box village of the TV series.

All the movies emphasize the smallness of the village: everyone knows Grace's situation before she does, everyone knows that Bamford's divorce has been finalized. There's also, particularly in Doc Martin, the small-mindedness of the village folk who are suspicious of outsiders. All of these tropes get called up for use in the TV show.

But what emerges most powerfully as a storytelling tool from all three movies is the transformative power of the Village. The banker who looks out over the London cityscape as he tries to reclaim the mortgage on Grace's house is transformed by the village into a happier man, who also becomes the village's new pot dealer after Matthew retires. The French gangster marries Grace and settles into a quieter life. Martin Bamford transforms from an isolated and lonely young man into a member of a supportive community.

The village also expels those who resist transformation, such as the customs agents and the grasping and greedy Bowden family. By and large, though, the notion that the village is a place that can soften hardened characters is certainly one carried through into the series.

The Doc Martin solo capers were successful enough to secure a deal with Sky Pictures for more movies, but Sky's shutdown ended that hope. Still, it probably seemed a shame to have all that production scaffolding in place and not do something with it. So Buffalo Pictures shopped the idea to ITV, which preferred the idea of a series to the original plan of two self-contained movies a year. ITV had another suggestion: make the character more of a "fish out of water." [To be continued]